Bonefish

Albula vulpes

This elusive, silvery fish is prized among fishers, but because of restrictions and its many bones, it is often released instead of brought in as food. These hard-to-find ‘gray ghosts’ appear dark blue-green from above with silver sides streaked with darker grey. Due to their feeding habits, they carry a minor risk of ciguatera poisoning to humans who eat them.

Order – Albuliformes

Family – Albulidae

Genus – Albula

Species – vulpes

Common Names

Commonly, bonefish are named for the many fine bones they contain. English common names include banana, bananafish, Indo-Pacific bonefish, ladyfish, round jaw, salmon peel, tarpon, tenny, and tenpounder. Other common names include albula (Polish), albule (French), albulid (Swedish), banane (French), banane de mer (French), banang (Malay), beenvis (Afrikaans), bending curut (Javanese), bidbid (Tagalog), bonouk (Arabic), bulat daun (Malay), carajo (Spanish), chache (Swahili), colepinha malabu (Creole), colvino (Spanish), conejo (Spanish), damenfisch (German), far al bahar (Arabic), frauenfisch (German), gatico (Spanish), gato (Spanish), hermaanchi (Papiamento), inliaula (Spanish), ioio (Tahitian), juruma (Portuguese), kifimbo (Swahili), kiokio (Tuamotuan), lasca (Portuguese), lasca boca redonda (Portuguese), liguija (Spanish), macabi (Spanish), macabi del helbra (Spanish), macabie (Spanish), macaco (Spanish), mnyimbi (Swahili), mursani (Portuguese), naiskala (Finnish), nginaan (Wolof), nifa (Tuamotuan), osso (Portuguese), panya (Swahili), parra (Spanish), peixe-banana (Portuguese), peje gato (Spanish), pepisang (Malay), raton (Spanish), raton de mar (Spanish), sanducha (Spanish), sorte de mulet (French), soto-iwashi (Japanese), suld (Palauan), tarr (Arabic), te ikari (Kiribati), te kiokio (Tuvaluan), ten-pounda (Creole), yu (Kumak), and zorro (Spanish).

Importance to Humans

In Florida, the commercial sale of bonefish is prohibited. Per regulations passed by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission in 2013, bonefish caught by recreational fishers must be released. This minimum length is less than the minimum length that the female must reach to be sexually mature. However, like the tarpon, permit, and other gamefish of the western Atlantic, bonefish provide the base for a large charter industry in Florida, the Bahamas, and throughout the Caribbean. Thus, most bonefish guides and anglers esteem the bonefish to such a degree that bonefish are nearly always released unharmed. Most mortality attributed to human activity occurs from injuries incurred when being landed, such as “gut hooking” or sharks that take advantage of the hooked fish. Although this is considered an important game fish, the flesh is bony and not highly prized.

Danger to Humans

Bonefish pose no threat to humans, though ciguatera poisoning may result if eaten.

Conservation

Other than the size and bag limits listed above, the bonefish is not listed as endangered or vulnerable with the World Conservation Union (IUCN).

> Check the status of the bonefish at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species. However, although local bonefish populations may not be affected by overfishing thanks to widespread catch and release practices, the fish may suffer from post-release mortality and poor water quality.

Geographical Distribution

Bonefish inhabit tropical and warm temperate waters worldwide, Although western Atlantic bonefish are occasionally taken as far north as North Carolina, New York, and New Brunswick, this species is most plentiful in south Florida, the Bahamas, and Bermuda. To the south, they range throughout the Caribbean Sea to Brazil. On the eastern Pacific coast, the bonefish occurs from San Francisco Bay, California, south to Peru and west to Hawaii.

Habitat

Bonefish are predominately a coastal species, commonly found in intertidal flats, mangrove areas, river mouths, and deeper adjacent waters. The flats vary in composition from sand or grass to rocky substrates. Bonefish can tolerate the oxygen-poor water they sometimes encounter in coastal habitats by inhaling air into a lung-like air bladder. Bonefish typically school, sometimes in groups of up to 100 individuals. Studies in the Bahamas using ultrasonic telemetry demonstrated the daily patterns of bonefish consist of a movement to shallow water during the rising tide, and a retreat into deeper water during a falling tide. Bonefish are also known to move from particular sites (creek, channel, bay, etc.) after inhabiting the location for a maximum period of several days. Over the long-term movements between such “favorite” sites seem to occur without any discernible pattern. During summer months, larger individuals tend to remain in deep water, rarely moving onto the flats; they reappear in autumn, as water temperatures grow cooler.

Biology

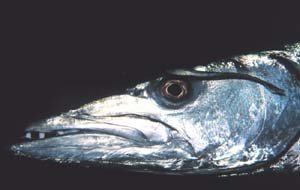

One of the most distinctive characteristics of the bonefish is the inferior mouth and conical nose that protrudes a third of its length beyond the mandible. The body is slender, round, and compressed, more so in large specimens than in young adults. The dorsal profile is more convex than the ventral profile. The first few rays of the dorsal fin are higher than the following rays and this lends a somewhat triangular shape to the dorsal fin when erect. The caudal fin is deeply forked, with the upper lobe slightly larger than the lower.

Coloration

Bonefish appear blue-greenish above, with bright silver scales on the sides and below. Dark streaks run in between the rows of scales, predominantly on the dorsal side of the body. The dorsal and caudal fins have dusky margins. Bonefish have no spines. Juvenile bonefish exhibit a series of nine dark crossbands on their backs. These bands extend nearly to the lateral line, with the third band crossing at the origin of the dorsal fin. Bands four and five are found under the posterior base of the dorsal fin. As the juvenile bonefish age the bands begin to disappear with the posterior bands the first to fade. Beyond about 3 inches (7.5 cm) the dark longitudinal streaks characteristic of the adults begin to appear and the last of the crossbands become obscured.

Dentition

Granular teeth, forming specialized dental plates, cover the tongue and upper jaw of the bonefish. Similar grinders are also present in the throat. The bonefish uses these modified teeth to grind its mollusk and crustacean prey.

Size, Age, and Growth

In the Caribbean Sea and western Atlantic Ocean, the bonefish reaches a maximum length of about 31 inches (77 cm) and a weight of 13 or 14 pounds. Floridian and Bahamian fish often range from 4-6 pounds (1.8-2.7 kg), with fish over 8 pounds (3.6 kg) regarded as large. However, bonefish taken from Africa and Hawaii may attain weights over 20 pounds (9.1 kg). Bonefish reach sexual maturity between 3 and 4 years of age, at which point they are typically between 17 and 19 inches (43-48 cm) in length. Bonefish may live in excess of 19 years.

Food Habits

The bonefish uses its conical snout to dig through the benthos to root up its prey, which it crushes and grinds with its powerful pharyngeal teeth. Bonefish feed on benthic and epibenthic prey, often in water less than 30 cm (12 inches) in depth. In south Florida, the prey consists primarily of crustaceans (xanthid crabs, portunid crabs, alphiid shrimp, penaeid shrimp), mollusks (clams and snails), polychaete worms, and fishes (primarily the gulf toadfish, Opsanus beta). The gulf toadfish is commonly found in the stomachs of larger bonefishes. Bahamian populations of bonefish appear to feed more heavily upon bivalves than do Florida Keys bonefish. Bonefish forage primarily on the flats, entering shallow water on rising tides. While in motion, schooling bonefish travel at the same speed and at a constant distance from each other. When feeding, the bonefish disperse slightly from the school but will reunite if frightened, again traveling in a patterned formation. Bonefish do not always travel in schools, but may also be found singly or in pairs. Schools of similar sized fish may consist of 4-6 individuals, or may number in the tens or hundreds. Large adult specimens are solitary.

Reproduction

Bonefish spawning occurs year round. Sexual maturity is reached at two years and near ripe females may be as small as 9 inches (25 cm). In the Florida Keys, bonefish spawn in deep water where currents can easily disperse the developing eggs and larvae to other locations. Bonefish are less reproductively active during the hotter summer months, while spawning peaks from November through June. Bonefish possess a leptocephalus larval stage, a reproductive strategy seen elsewhere only amongst the closely related tarpons and eels. The transformation from the transparent, ribbon-like leptocephalus to juvenile bonefish occurs in three distinct stages. Early stage 1 leptocephali lack dorsal, anal, and pectoral fins and are small, usually less than about 30mm. Late in stage 1 the nascent dorsal and anal fins appear and the larvae approaches its maximum size of approximately 63mm. At this length the larvae begins a rapid metamorphosis in which the entire body shrinks for 10-12 days until it reaches half its original length. During this transformation (stage II) the anal and dorsal fins move forward and the snout projects noticeably beyond the mandible. The subsequent appearance of scales, the lateral line, and the onset of an overall appearance of that of a miniature bonefish mark the transformation to a fry (stage III). Pigmentation and crossbands appear at about 4 cm in length, followed by the appearance of longitudinal stripes and the disappearance of the crossbands.

Predators

Sharks and barracuda often prey on bonefish. Bonefish are built for speed out of necessity, as the only defense they have is to flee their predators. Bonefish are alert and wary; whole schools may be easily spooked, making them difficult for fishers to catch.

Taxonomy

Linnaeus described the bonefish in 1758, designating it a species within the genus Esox, a taxon that at the time already referred to at least one species of the holarctic freshwater pikes and pickerels. Recognizing the conflict, later workers placed the bonefish in the available genus Albula. The scientific name Albula vulpes is derived from Latin, and can be translated as “white fox”. Other synonyms of Albula vulpes include, Esox argenteus, Albula conorynchus, Albula plumier, Amis immaculata, Clupea brasilienses, Clupea macrocephala, Butyrinus bananus, Engraulis sericus, Engraulis bahiensis, Glossodus forskalii, Albula goreensis, Albula parrae, Albula seminuda, Albula rostrata, Esunculus costai,Atopichthys esunculus, and Albula virgata. At least one other species of bonefish exists, the shafted bonefish, described and named by Fowler as Dixonina nemoptera in 1911. However, some scientists argue that the differences between the two species do not warrant genetic separation, and that both should be included within the genus Albula.

Prepared by: Sean Morey