Thresher Shark

Alopias vulpinus

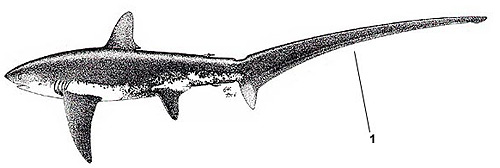

These sharks are easily recognized by the long upper lobe of the caudal fin (top half of the tail), which they use to stun their prey, usually smaller schooling fish. They are fast swimmers that will sometimes leap out of the water. Because they have small mouths and teeth, and are quite timid, they are considered mostly harmless to humans.

Order – Lamniformes

Family – Alopiidae

Genus – Alopias

Species – vulpinus

Common Names

This shark is known as the thresher shark, common thresher, fox shark, sea fox, swiveltail, and thrasher. Internationally, this shark is referred to as pez zorro (Spanish), cação-pena (Portuguese), faux (French), fuchshai (German), aleposkylos (Greek), big-eye thresher (English), budenb (Maltese), cacao-raposa (Portuguese), chichi espada (Spanish), coleto (Spanish), coludo (Spanish), coludo pinto (Spanish), drescherhai (German), grayfish (English), grillo (Spanish), guadaña (Spanish), guilla (Catalan), jarjur (Arabic), kalb (Arabic), karage (Swahili), kettuhai (Finnish), Kosogon (Polish), K’wet’thenéchte (Salish), Langschweif (German), Loup de mer (French), mango-ripi (Maori), ma’o aero (Tahitian), mao-naga (Japanese), papa kinengo (Swahili), pas lisica (Serbian), pating (Tagalog), pèis rato (French), peixe-rato (Portuguese), peje sable (Spanish), peje zorra (Spanish), pejerrabo (Spanish), pesce volpe (Italian), peshkdhelpën (Albanian), pez espada (Spanish), pez palo (Spanish), pichirata (Spanish), pixxivolpi (Maltese), poisson-épée (French), psina lisica (Serbian), qatwa al bahar (Arabic), rabilongo (Portuguese), rabo de zorra (Spanish), rævehaj (Danish), raposa (Spanish), raposa marina (Spanish), raposo (Portuguese), rävhaj (Swedish), rechin-vulpe (Rumanian), renard (French), renard de mers (Creole), renard marin (French), requin renard (French), revaháur (Faroese), revehai (Norwegian), romano (Portuguese), romão (Portuguese), sapan (Turkish), sapan baligi (Turkish), seefuchs (German), singe de mer (French), skylópsaro (Greek), squalo volpe (Italian), tærsker (Danish), te bakoa (Kiribati), te kimoa (Kiribati), thintail thresher (English), thon blanc (French), tiburón zorro (Spanish), tubarão raposo (Portuguese), volpe de mar (Italian), voshaai (Dutch), watwa albahar (Arabic), whip-tailed shark (English), zoro cauda longa (Portuguese), zorro (Spanish), and zorro blanco (Spanish).

Importance to Humans

The meat and the fins have good commercial value. Their hides are used for leather and their liver oil can be processed for vitamins. When found in groups, threshers are a nuisance to mackerel fisherman because they become tangled in their nets.

Threshers have been widely caught in offshore longlines by the former USSR, Japan, Taiwan, Spain, Brazil, Uruguay, USA and other countries. The northwestern Indian ocean and eastern Pacific are especially important fishing areas. A drift net fishery for the shark developed in southern California; however, the stock was rapidly overfished. It is classed as a game fish and sportsmen in the USA and South Africa fish them. They are often hooked on the upper lobe of the caudal fin. This occurs when the sharks try to stun live bait with their caudal fin. Threshers put up an energetic resistance and often succeed in freeing themselves.

Danger to Humans

The thresher shark is considered harmless. The species is shy and difficult to approach. Divers that have encountered these sharks claim that they did not act aggressively. However, some caution should be taking considering the size of these sharks. They have been known to attack boats.

Conservation

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Check the status of the thresher shark at the IUCN website.

The threshers are an abundant and globally distributed species; however, there is some concern due to results of the Pacific thresher fishery where the population declined rapidly despite a small and localized catch. The thresher is vulnerable to overfishing in a short period of time. Lack of data from other locations have made it difficult to access population fluctuations at an international level.

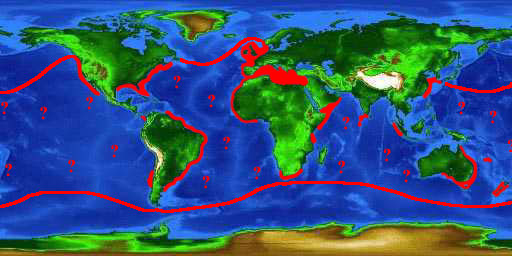

Geographical Distribution

The thresher shark, an oceanic and coastal species, inhabits tropical and cold -temperate waters worldwide. It is most common in temperate waters. In the Atlantic Ocean, it ranges from Newfoundland to Cuba and southern Brazil to Argentina, and from Norway and British Isles to Ghana and Ivory Coast, including the Mediterranean Sea. Although it is found along the entire U.S. Atlantic coast, it is rare south of New England. In the Indo-Pacific region, it is found off South Africa, Tanzania, Somalia, Maldives, Chagos Archipelago, Gulf of Aden , Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Sumatra, Japan , Republic of Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and New Caledonia. The thresher shark is also found in the Society Islands, Fanning Islands, and Hawaiian Islands. In the eastern Pacific Ocean it occurs off the coast of British Columbia to central Baja California, Panama south to Chile.

Habitat

The thresher shark is a pelagic species inhabiting both coastal and oceanic waters. It is most commonly observed far from shore, although it wanders close to the coast in search of food. Adults are common over the continental shelf, while juveniles reside in coastal bays and near shore waters. It’s mostly seen on the surface but it inhabits waters to 1,800 feet (550 m) in depth. Thresher sharks are observed infrequently jumping out of the water. Threshers are considered a highly migratory species in the U.S. by the National Marine Fisheries Service for fishery management purposes.

Distinguishing Characteristics

1. Sickle-shaped caudal fin with extremely long upper lobe (about half the total body length)

Biology

Distinctive Features

The thresher shark can be easily identified by the long upper lobe of the caudal fin. The lobe can be as long as the body and gives the tail a slender “whiplike” appearance. It has a moderate size eye and a first dorsal fin free rear tip located ahead of the pelvic fins. The pectoral fins are falcate and narrow tipped. The sides above the pectoral-fin bases are marked with a white patch that extends forward from the abdominal area.

The bigeye thresher (Alopias superciliosus) is similar to this species; however, it has an enormous vertically oval eye, a v-shaped ridge on the head, a longer snout, and fewer teeth. Also, the free rear tip of its dorsal fin reaches behind the pelvic fin origin.

The pelagic thresher (Alopias pelagicus) also resembles the thresher shark, but its head is narrower, snout is more elongated and the pectoral fins are nearly straight and broad tipped.

Coloration

Threshers are usually dark brown and slate gray but can be almost completely black. They are white on their underside, but have dark spots near the pelvic fin and the caudal peduncle. The white color can extend above the pectoral fins onto the head.

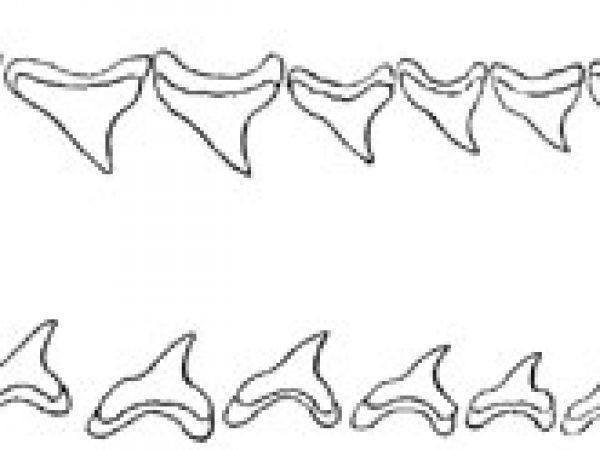

Dentition

Threshers have small, blade like, smooth edge-curved teeth. There are 20 teeth on either side of the upper jaw and 21 teeth on either side of the lower jaw. The two jaws have similar teeth with each successive tooth becoming increasingly oblique with outer margins increasingly deeply concave.

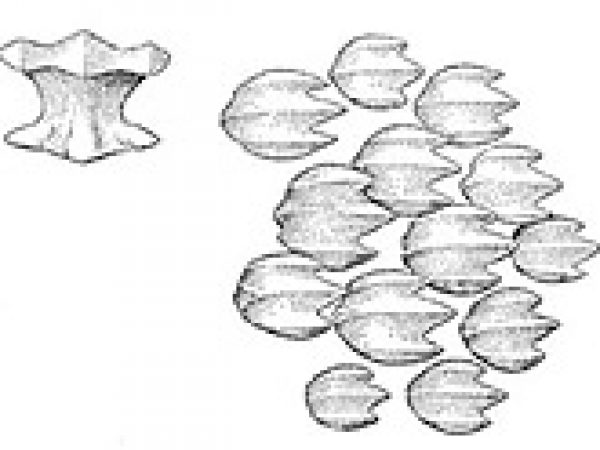

Denticles

The dermal denticles are closely overlapping and very small (.2 x .21 mm). The blades are horizontally small and have moderately long pedicels.

Size, Age, and Growth

Male thresher sharks mature at about 10.5 feet (330 cm ) and females at around 8.5 – 14.8 feet (260 – 450cm). They are about 5 feet (150 cm) long at birth and grow 1.6 feet (50 cm) a year as juveniles. Adults grow about 0.3 feet (10 cm) a year. The maximum reported length of the thresher shark is 24.9 feet (760 cm), and the maximum weight recorded is over 750 lbs (340 kg) .

Food Habits

Bony fish make up 97% of the thresher’s diet. They feed mostly on small schooling fish such as menhaden, herring, Atlantic saury, sand lance, and mackerel. Bluefish and butterfish are the most common meal. They also feed on bonito and squid. Thresher sharks encircle schools of fish and then stun the prey with their tails. This is often done in groups and/or pairs. They have also been known to kill sea birds with their tails.

Reproduction

The thresher shark is an ovoviviparous species, meaning it develops without a placental attachment. The embryos feed on eggs passed into the uterus. Approximately two to four young develop with each pregnancy. Size at birth is usually between 3.7- 5.0 feet (114-160 cm) and 11 – 13 lbs (5-6 kg), corresponding directly with the mother’s size. The caudal fin is proportionally as long in the embryo as it is in the adult. They reproduce annually and are thought to reproduce throughout the species range.

Predators

Larger sharks prey upon juveniles, but adult threshers have no known predators.

Parasites

Nine species of copepods, genus Nemesis, parasitize thresher sharks. These parasites attach themselves to gill filaments, and can cause tissue damage. This damage to the gill filaments can cause respiration impairment in the segments of the gills.

Taxonomy

The thresher shark was first described by Bonnaterre in 1788, as Squalus vulpinis and was later changed to the current name of Alopias vulpinus (Bonaterre, 1788). Vulpinus is derived from vulpes, which means “fox” in Latin. Synonymous names include Squalus vulpes Gmelin 1789, Alopias macrourus Rafinesque 1810, Galeus vulpecula Rafinesque 1810, Squalus alopecias Gronow 1854, Alopecias barrae Perez Canto 1886, Alopecias chilensis Philippi 1901, Alopecias longimana Philippi 1901, Vulpecula marina Garman 1913, Alopias caudatusPhilipps 1932, and Alopas greyi Whitely 1937.

Prepared by: Vanessa Jordan