Oceanic Whitetip Shark

Carcharhinus longimanus

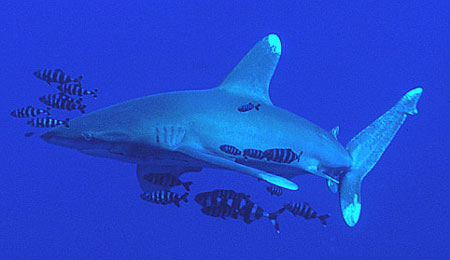

This large shark is readily recognized by its long white-tipped paddle-like pectoral fins and rounded first dorsal fin (Compagno et al. 2005). Solitary and slow moving, it prefers the upper layers of deep-water areas, where it is an opportunistic hunter (Baum et al. 2015). Oceanic whitetip sharks are one of the more dangerous sharks to humans. They are known to have attacked survivors of ship and plane wrecks at sea, and are suspected to be responsible for several unrecorded human fatalities (ISAF 2018).

The oceanic whitetip is the primary species implicated in the shark bites surrounding the sinking of the USS Indianapolis in 1945, also known as the “worst shark attack in history” (ISAF 2018). See article in the Palm Beach Post.

Order: Carcharhiniformes

Family: Carcharhinidae

Genus: Carcharhinus

Species: longimanus

Common Names

Africaans: Opesee-wittiphaai

English: Oceanic whitetip shark, Nigano shark, Whitetip, Whitetip shark, Whitetip whaler

Carolinian: Yeshalifes

Dutch: Oceanische witpunthaai

Finnish: Valkopilkkahai

French: Rameur, Requin à aileron blanc, Requin blanc, Requin canal

German: Hochsee-Weißspitzenhai, Weißspitzenhai

Italian: Squala alalunga

Japanese: Yogore

Malay: Ikan yu

Polish: Zarlacz bialopletwy

Portuguese: Galha branca, Marracho, Marracho oceánico, Marracho-de-pontas-brancas

Samoan: Apoapo

Spanish: Cazón, Galano, Tiburon oceanico

Tagalog: Pating

Tahitian: Parata

Turkish: Köpek baligi

Importance to Humans

Shark fishers use longlines and drift nets set in the open ocean to catch oceanic whitetip sharks (Baum et al. 2015). The meat is marketed fresh, frozen, smoked, and dried-salted for human consumption, while the skin is used for leather, fins for shark-fin soup and the liver oil for vitamins (Ebert and Stehmann 2013). The meat is also processed into fishmeal. Tuna fishermen dislike the oceanic whitetip sharks as they frequently follow tuna boats and damage or consume the catch (Baum et al. 2015).

Danger to Humans

Although primarily found offshore, the oceanic whitetip is considered potentially dangerous to humans. It is often the first species seen in waters surrounding mid-ocean disasters. During both World Wars, the oceanic whitetip shark was a major concern for torpedoed boats and downed planes. When the Nova Scotia steamship was sunk by torpedoes from a German submarine off the coast of South Africa, close to 1,000 men were on board, however only 192 survived. It is believed that many of the fatalities were victims of the oceanic whitetip shark in what eyewitness accounts described as a “feeding frenzy” (Bass et al. 1973). In encounters with divers, ocean whitetip sharks show little fear and are often quite persistent circling around divers in the water. Due to this shark’s opportunistic feeding behavior, size and unpredictability around divers, this species should be treated with extreme caution (Compagno et al. 1984). There are recorded cases in which potential attacks may have been averted by quick action on the part of divers who have struck the sharks on the snout to dissuade curiosity (ISAF 2018).

View shark attacks by species on a world mapConservation

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable

This species has suffered sharp declines from historical levels. It used to be both broadly distributed and highly abundant throughout the world’s oceans. Its numbers have declined precipitously over the past 30 years as a consequence of being caught as bycatch in tuna fisheries and because of direct targeting for their fins which are highly prized in the Asian fin trade. Documented declines have been particularly acute in the Northwest and Western Central Atlantic (Baum et al. 2015). Globally there is less data available, but it is likely that similar pressures are exerted on this species all over the world.

> Check the status of the oceanic whitetip shark at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

Geographical Distribution

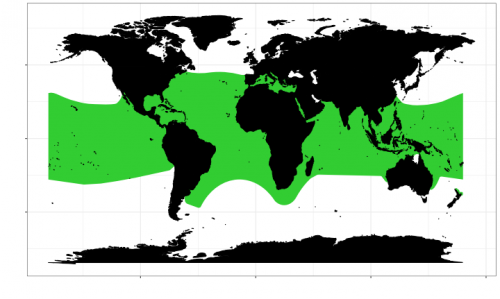

The oceanic whitetip shark is distributed worldwide in epipelagic tropical and subtropical waters between 30°N and 35°S latitude (Baum et al. 2015). It ranges from Maine, U.S. south to Argentina in the western Atlantic Ocean and from Portugal to South Africa and the Mediterranean in the eastern Atlantic. In the Indo-Pacific this species is found from the Red Sea and East Africa across SE Asia though the central pacific (Hawaii, Samoa, Tahiti and the Tuamoto Islands) over to eastern Pacific where it can be found from southern California, in the U.S.A south to Peru and the Galapagos (Compagno et al. 1984). The 1995 UN Agreement on the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks (UNFSA) considers it a highly migratory species (Baum et al. 2015).

Habitat

The oceanic whitetip is usually observed well offshore in deep water areas (0-656 feet (0-200 m)) although on occasion it has been reported in shallower waters near land, usually near oceanic islands (Baum et al. 2015). Longline capture data in the Pacific Ocean shows that abundance of this shark increases with distance from land. The oceanic whitetip’s range includes water with temperatures between 64 to 82°F (18-28°C) (Compagno et al. 2005). Though previously considered one of the top three most abundant oceanic sharks, along with the blue shark (Prionace glauca) and the silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis), it is now only occasionally reported (Baum et al. 2015). This shark is primarily solitary, but also forms aggregations and has been observed in “feeding frenzies” when a food source is present. It is a slow swimmer showing equivalent activity during both daytime and nighttime hours. Reports have described swimming behavior in open waters at or near the surface of the water as moving slowly with the huge pectoral fins spread widely (Compagno et al. 2005).

Remoras, dolphin fishes, and pilot fishes often accompany oceanic whitetip sharks. It has also been observed swimming in association with the shortfin pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus) in Hawaiian waters (reported by Jeremy Stafford-Deitsch in 1988). Although the reason for such behavior is unknown, it is lkely to be food-related. Pilot whales are efficient at locating squid upon which the oceanic whitetip sharks also feed.

Distinguishing Characteristics

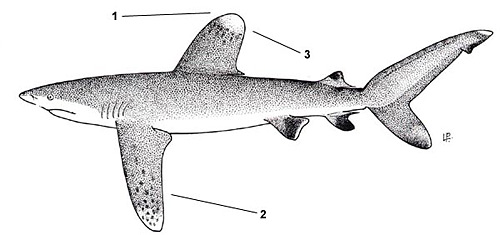

1. First dorsal fin is broadly rounded

2. Pectoral fins are long and paddle-shaped

3. First dorsal, pectoral, and caudal fins usually have white mottling on tips in adults

Biology

Distinctive Features

The oceanic whitetip shark is readily identified in the field. It is stocky has a large rounded first dorsal fin and very long and wide paddle-like pectoral fins. The head of this shark includes a short and bluntly rounded nose and circular eyes. The first dorsal fin is very large with a rounded tip, originating just in front of the free rear tips of the pectoral fins. The second dorsal fin originates over or slightly in front of the anal fin origin. (Compagno et al. 2005).

Coloration

This species is commonly named the oceanic whitetip shark for the mottled white-tipped first dorsal, pectoral, pelvic, and caudal fins. These white markings are sometimes accompanied black markings in young individuals. There may also be a dark saddle-shaped marking present between the first and second dorsal fins. The body of the oceanic whitetip shark is grayish bronze to brown in color dorsally, varying depending upon geographical location. The underside is white (Compagno et al. 2005).

Dentition

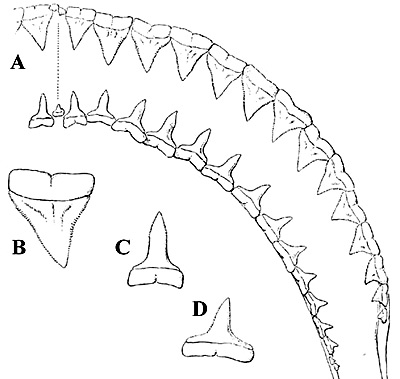

The upper jaw contains broad, triangular, serrated teeth, while the teeth in the lower jaw are more pointed and are only serrated near the tip (Compagno et al. 1984). These teeth, located in powerful jaws, are effective at holding and tearing prey. The arrangement of the teeth is 14 or 15 on each side of the symphysis of the upper jaw and 13-15 teeth on either side of the lower jaw symphysis (Compagno et al. 1984). The teeth are most easily confused with Bull shark, and Dusky shark teeth both of which are broadly triangular and strongly serrated.

Denticles

The dermal denticles of the oceanic whitetip shark lie almost flat resulting in a smooth-to-the-touch skin. The denticles overlap only slightly with some skin exposed. Usually having 5, but sometimes 6 or 7, ridges, the denticles are broader than long (Castro 2011).

Size, Age, and Growth

Oceanic whitetip sharks grow to large sizes, with some individuals reaching 11-13 feet (3.5-4 m). However, most specimens are less than 10 feet (3 m) in length (Baum et al. 2015). The maximum recorded weight for this species is 370 pounds (167.4 kg) (IGFA). Males and females mature at similar sizes of about 5.6-6.2 feet (1.7-1.9 m) in length, both corresponding to an age of 4 to 5 years (Baum et al. 2015).

Food Habits

The oceanic whitetip shark feeds on bony fishes including lancetfish, oarfish, barracuda, jacks, dolphinfish, marlin, tuna, and mackerels. Other prey consists of stingrays, sea turtles, sea birds, gastropods, squid, crustaceans, and carrion (dead whales and dolphins) (Compagno et al. 2005). Feeding behavior reported for this shark includes biting into schools of bony fishes including yellowfin and big-eye tuna. The oceanic whitetip shark has been observed eating garbage that is disposed of at sea. If other shark species encounter the oceanic whitetip during feeding activities, the oceanic whitetip is usually dominant (Compagno et al. 2005).

Reproduction

Records indicate the oceanic whitetip shark mates during the early summer months in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean and the southwestern Indian Ocean. This shark is viviparous. Embryos are nourished by a placental yolk-sac attached to the uterine wall by umbilical cords. After a 10-12 month gestation period, 1 to15 pups are born. The number of pups in a litter appears to be correlated with the size of the mother (Compagno et al. 2005). Each pup is approximately 24-25.6 inches (60-65 cm) in length at birth (Baum et al. 2015).

Predators

Large sharks are potential predators of the oceanic whitetip shark, especially immature individuals.

Taxonomy

Cuban naturalist Felipe Poey originally described the oceanic whitetip shark as Squalus longimanus in 1861, followed by a name change to Pterolamiops longimanus and then to the currently valid name of Carcharhinus longimanus. The genus name Carcharhinus is derived from the Greek “karcharos” = sharpen and “rhinos” = nose. The species name longimanus is translated as long fingers for the characteristic long paddle-like pectoral fins. Synonyms used to refer to this species in past scientific literature include Carcharius obtusus Garman 1881, Carcharius insularum Snyder 1904, Pterolamiops magnipinnis Smith 1958, and Pterolamiops budkeri Fourmanoir 1961.

References

Bass, A.J., D’Aubrey, J.D. and Kistnasamy, N. 1973. Sharks of the east coast of southern Africa. V. The families Hexanchidae, Chlamydoselachidae, Heterodontidae, Pristiophoridae and Squatinidae. South African Association for Marine Biological Research, Oceanographic Research Institute Investigational Report No. 43.

Baum, J., Medina, E., Musick, J.A. & Smale, M. (2015). Carcharhinus longimanus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T39374A85699641. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015.RLTS.T39374A85699641.en.

Castro, J.I. (2011). The Sharks of North America. Oxford University Press, USA: pp. 438-440.

Compagno, L.J.V. 1984. FAO species catalogue. Vol. 4. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125, Volume 4, Part 1.

Compagno, L., Dando, M., & Fowler, S. (2005). A Field Guide to the Sharks of the World. London: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

EBERT, D.A. & STEHMANN, M. (2013). Sharks, batoids, and chimaeras of the North Atlantic. FAO Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes, 7. Rome, FAO: 523 pp.

Revised by Lindsay French and Gavin Naylor 2018

Original preparation by Cathleen Bester