Sand Tiger Shark

Carcharias taurus

Sand tiger sharks are large, slow-moving, coastal sharks that have a flattened, conical snout. They are light brown on the dorsal surface with some scattered dark spots, and light colored ventrally. They have broad triangular fins and a distinct caudal fin that is asymmetrical (heterocercal) in shape, with an enlarged upper lobe. Sand tigers prefer hunting fish and invertebrates inshore near reefs, surf, and shallow bays, and migrate north-south with the seasonal temperature changes. They produce two pups, one from each uterus, every other year (Compagno et al., 2005).

Fun Fact: Sand tiger embryos exhibit intrauterine cannibalism (adelphophagy). The largest or most developed embryo in each uterus eats the remaining eggs and less developed embryos (Pollard and Smith, 2009). See video on YouTube

Order: Lamniformes

Family: Odontaspididae

Genus: Carcharias

Species: taurus

Common Names

English language common names include sand tiger shark (US), grey nurse shark (Australia), ground shark, spotted raggedtooth shark (South Africa), slender-tooth shark, spotted sandtiger shark. Other common names are bacota (Spanish), pintado (Spanish), sarda (Spanish), cação-da-areia (Portuguese), mangona (Portuguese), tavrocarcharias (Greek), chien de mer (French), kalb, (Arabic), grauer sandhai (German), hietahai (Finnish), karish khol pari (Hebrew), oxhaj (Swedish), zandtijgerhaai (Dutch), peshkaqen i eger (Albanian), shirowani (Japanese) and spikkel-skeurtandhaai (Afrikaans).

Importance to Humans

Sand tigers are fished both commercially and recreationally throughout their range with variable importance regionally. In the North Pacific, northern Indian Ocean and off the tropical west coast of Africa, the sand tiger is part of the commercial fishery as a food fish. The meat is consumed, fresh, frozen and dried-salted. Fins are sold in oriental markets for shark fin soup and jaws and teeth are used for trophies and ornaments. In North American waters, the sand tiger was historically a part of the commercial fishery but received full protection under the Atlantic Fishery Management Plan in 1997. In Australia the sand tiger received protection in New South Wales in 1984 and in Queensland in 1997.

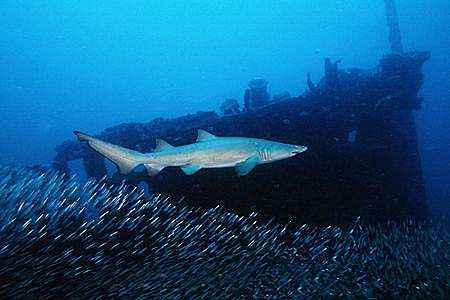

Sand tigers survive well in public aquaria and are a favorite because of their large size and fierce appearance. This species is common in coastal waters and can often be found around shipwrecks (Pollard and Smith, 2009).

Danger to Humans

While these animals are not aggressive unless provoked, their size and conspicuously protruding teeth demand respect. Special caution is needed when spearfishing as a handful of bites have occurred on spearfishers carrying speared fish. There are accounts of sand tigers stealing fish from stringers and spears underwater. In total, the ISAF has only 29 records of unprovoked sand tiger bites on humans, none have resulted in a fatality (ISAF 2018).

View shark attacks by species on a world mapConservation

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable

Sand tiger sharks are a prohibited species regulated in the commercial longline shark fishery on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States by the National Marine Fisheries Service. Any sand tiger caught must be released immediately with minimal harm to the shark. The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) classifies the sand tiger as “Vulnerable”, which means it faces a high risk of extinction in the wild in the medium term future. This is due to an observed, or estimated reduction in the population of at least 20% over the last 10 years or three generations. Catch rates of populations in Australia and South Africa have shown declines due to commercial fishing, spearfishing and beach meshing. Even with status as a protected species, the recovery of the sand tiger shark off the coast of Australia has been very slow (Pollard and Smith, 2009).

> Check the status of the tiger sand shark at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

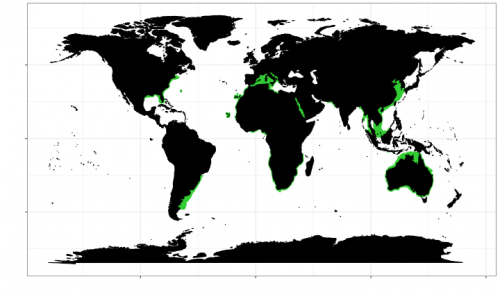

Geographical Distribution

The sand tiger shark can be found in most warm seas throughout the world except for the eastern Pacific. In the western Atlantic Ocean it ranges from the Gulf of Maine (U.S.A) to Argentina and is commonly found in Cape Cod (U.S.) and Delaware Bay (U.S.) during the summer months. In the eastern Atlantic, it ranges from the coast of Europe and the Mediterranean Sea down to South Africa In the Pacific it ranges from Australia to Japan (Pollard and Smith, 2009).

Habitat

Sand tigers are commonly found inshore ranging in depths from 6 to 626 feet (1.8 to 191 m). The sand tiger is found in a variety of habitats including the surf zone, shallow bays, coral and rocky reefs and deeper areas around the outer continental shelves. C. taurus is often found on the bottom but can also be seen at all levels in the water column. It is migratory within its region, moving poleward during the summer while making equatorial movements during the fall and winter months (Compagno et al. 2005).

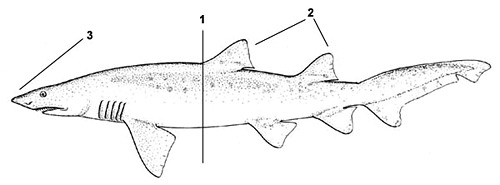

Distinguishing Characteristics

1. First dorsal fin is placed back on body, closer to pelvic fins than to pectoral fins

2. First and second dorsal and anal fins nearly equal in size

3. Snout flattened, with long mouth extending behind eyes

Biology

Distinctive Features

The sand tiger shark is a large, bulky shark with a flattened conical snout and a long mouth that extends behind the eyes. The first dorsal fin is set back and is much closer to the pelvic fins than the pectoral fins. The anal and dorsal fins are large and broad-based and the second dorsal fin is almost the same size as the first dorsal. Gill slits are anterior to the origin of the pectoral fins in this species. The caudal fin of the sand tiger shark is asymmetrically shaped with a strongly pronounced upper lobe.

Coloration

Coloration of the sand tiger shark is generally light brown or light greenish–gray above and grayish white below. Many individuals have darker reddish or brown spots scattered on the body.

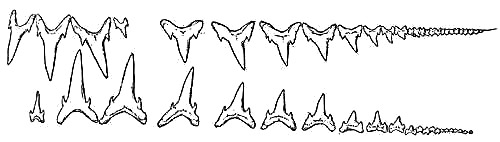

Dentition

The teeth of the sand tiger shark have long and narrow primary cusps with small lateral cusplets. The upper anterior teeth are separated by small intermediate teeth at the symphysis. The upper teeth number 44 to 48 and the lower teeth number 41 to 46. The teeth in the corners of the mouth are small and numerous. The ragged looking teeth give the sand tiger shark a menacing appearance.

Denticles

Dermal denticles are loosely spaced and ovoid lanceolate shaped with three ridges. The axial ridge is prominent and sharp-edged anteriorly but usually is subdivided and flat-topped posteriorly. In individuals around 3.3 feet (100cm) long denticle sizes are about 0.016 inches (0.4mm) broad by 0.018 inches (0.45mm) long.

Size, Age, and Growth

Average size ranges from four to nine feet with maximum length believed to be around 10.5 feet (320 cm) in females and 9.9 feet (301 cm) in males. Males and females mature at about 2 m (6.5 ft) in total length. Maximum age estimates based on vertebral centra are 30-35 years old but the oldest recorded individuals in aquariums have lived to be 16 years old.

Food Habits

The diet feeder consists primarily of a wide variety of bony fish including herring, bluefish, flatfish, eel, mullet, snapper, hake, porgie, croakes, bonito, remora, sea robin and sea bass. They also consume rays, squid, crab, lobster and other smaller sharks. Cooperative feeding has been observed by schools of sharks surrounding and bunching schooling prey prior to feeding on them.

Reproduction

Embryonic development is ovoviviparous with embryophagy occurring in the uteri. Usually only one pup survives in each uteri since the largest embryo ends up eating all of its smaller siblings during gestation. This generally limits litter sizes to two individuals. At 6.7 inches (17 cm) embryos have functional teeth and are feeding and at 10.2 inches (26 cm) they are able to move in utero. Gestation periods may be around nine to twelve months and pups generally measure 39 inches (99 cm) at birth.

Predators

Juveniles are susceptible to predation by larger sharks. Mature individuals have no major predators.

Distinctive Behavior

Since the sand tiger shark is denser than water and lacks a swim bladder like bony fish, it has adopted a behavior that allows it to become neutrally buoyant in the water column. The shark comes to the surface and gulps air, which it holds in its stomach. This allows the shark to hover motionless in the water.

Taxonomy

The sand tiger shark was originally named Carcharias taurus by Rafinesque in 1810. Since then it has also been referred to literature as Odontaspis taurus Rafinesque 1810, Eugomphodus taurus Rafinesque 1810, Odontaspis americanus Mitchill 1815, Squalus americanus Mitchill 1815, Carcharias griseus Ayres 1843, Odontaspis arenarius Ogilby 1911, Carcharias arenarius Ogilby 1911, Odontaspis platensis Lahille 1928, and Carcharius platensisLahille 1928.

References

Compagno, L., Dando, M., & Fowler, S. (2005). A Field Guide to the Sharks of the World. London: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

Pollard, D. & Smith, A. 2009. Carcharias taurus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2009: e.T3854A10132481. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009-2.RLTS.T3854A10132481.en

Revised by Lindsay French and Gavin Naylor 2018

Original preparation by Peter Cooper