Southern Stingray

Dasyatis americana

These diamond-shaped rays are olive-brown to green-grey on top and creamy white underneath. Their pectoral fins can grow up to a total width of 79 inches, which they use to stir up the sandy ocean floor to either reveal crustaceans and small fish, or bury themselves to hide from predators or prey. Their tails can be up to twice as long as their bodies, with a sharp spine that has teeth on either side of it. Although rays can be docile and friendly to humans, they scavenge the surf zone for food, and it is common for humans to step on them and get injured by their sharp spine.

Order – Myliobatiformes

Family – Dasyatidae

Genus – Dasyatis

Species – americana

Common Names

Common English names include southern stingray, kit, stingaree, stingray, and whip stingray. Other names are amerika-aka-ei (Japanese), chuchu rok (Papiamento), ignelivatoz (Turkish), ogoncza amerykanska (Polish), pastenague americaine (French), pijlstaartrog (Dutch), Raia-cravadora (Portuguese), raya (Spanish), raya verde (Spanish), ruskokeihäsrausku (Finnish), stechrochen (German), stekelrog (Dutch), stingrocka (Swedish), trigono (Italian), and volina (Serbian).

Importance to Humans

Research is being conducted by the biomedical and neurobiological industries on the venomous component of the tail spine and its possible future use in applications within these fields. Stingrays are of considerable importance to ecotourism, with D. americana often featured in dives such as at “Stingray City” in the Cayman Islands. Native people in Polynesia, Malaysia, Central America, and Africa have used stingray spines to make spears, knives, and other useful tools.

Danger to Humans

The southern stingray is a non-aggressive animal, posing little threat to humans. However, when stepped on, the ray will use its spine in defense.

Conservation

This stingray is listed as “Data Deficient” with the World Conservation Union (IUCN).

> Check the status of the southern stingray at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

Geographical Distribution

This stingray occurs in tropical and subtropical waters of the southern Atlantic Ocean, as well as the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. It is most abundant near Florida and the Bahamas.

Habitat

Like many other rays, D. americana prefers shallow coastal or estuarine habitats with sand/silt bottoms, although they have been observed in depths to 180 feet (53 m). As a bottom dweller, the southern stingray avoids walls and large reef structures where it is difficult to feed. These rays have been netted in water temperatures ranging from 82-90°F (28-32 °C), and at depths of 12 feet (3.7 m). These animals have been observed alone, in pairs, and less frequently in large aggregations.

Biology

Distinctive Features

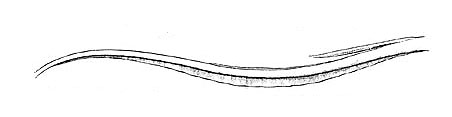

The flattened pectoral fins form a disc that continues anterior to the head and posterior to the pelvic region. The disc of D. americana is diamond-shaped, making it more angular than discs of other rays. The head is elevated and contains spiracles that enable the ray to take in water dorsally while lying on the seabed. The gills, which expel water, are located ventrally. The disc is approximately 1.2 times as broad as it is long. The tail is rounded anterior to the spine. Posterior to the spine, the tail is flattened dorsoventrally. The dorsal tail fold is extremely reduced, while the ventral fold is highly developed. The ventral fold originates directly below the tail spine and extends posteriorly almost to the tip of tail. The tail, measured from the cloaca to the tip, can reach lengths twice as long as the body measured from cloaca to the tip of snout. As with other rays, the tail spine of D. americana is thought to be derived from modified scales. The distance between the outer margins of the eye orbits approximates tail spine length. The spine is round, but slightly flattened dorsoventrally with 52-80 teeth on either side.

Coloration

Dorsal coloration varies between dark gray, green, and brown. Ventral coloration is predominantly white with dorsal coloration often bleeding over the edges of the disc onto the ventral surface. Color intensity may decrease around the head region.

Dentition

Southern stingrays have multiple rows of teeth that are relatively uniform in size except for somewhat smaller teeth near the outer corners of the mouth. Females and immature males have teeth that are tetragonal with rounded corners. Teeth of mature males have low conical cusps.

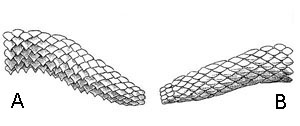

Denticles

Dermal denticles, characteristic of elasmobranchs, are sporadic in Myliobatiformes. As the ray develops, tubercles form sporadically on the disc. Tubercles are modified scales that slope anteriorly and point posteriorly. They are present from the nuchal region down the midpoint of the midline and begin to decrease again posteriorly. Smaller tubercles also occur at the shoulder region, between the eye orbits and spiracles. Larger specimens may have small tubercles in the tail spine region. Tubercles on females are typically more pronounced and densely packed than those on males.

Size, Age & Growth

The southern stingray reaches a maximum disc width of 79 inches (200cm) and weight of 214 lbs (97 kg). Little is known about its average life span and growth rate.

Food Habits

Feeding constantly during the day and night, D. americana feeds on large epibenthic prey such as teleosts and crustaceans. Other prey include stomatopods, mollusks, and annelids. It feeds by slowly grazing along the sandy ocean floor, relying on electro-reception combined with a strong sense of smell and touch.

Reproduction

Males become sexually mature at 20 inches (51cm) disc width (DW), while females mature at 29.5-31.5 inches (75-80cm) DW. A captive study has indicated a biannual reproductive cycle, however, this is still under investigation. As with other rays, development of D. americana occurs through aplacental viviparity. The embryo subsists on a yolk sac for nourishment early in development. When the yolk sac is absorbed, nourishment is provided through uterine milk from maternal secretions rather than via a placenta. Gestation takes 4-11 months and litter sizes range from 2-10 pups, with an average of 4 pups per litter. Unlike D. sabina, there is a direct correlation between litter size and size of the female. Pup size in captivity ranges from approximately 7.9 to 13.4 inches (20-34 cm) DW and weight varies from 0.6 to 2.5 lbs (282-1128 g). The pups have long, slender tails and broad wing-like pectoral fins at birth.

Predators

D. americana is preyed on by many species of sharks and other large fishes.

Parasites

While trematode ectoparasites are common on these stingrays, infestation is not prolific. However, the overall parasite load for D. americana, as for many elasmobranchs, can be extensive. As a result, they have been observed to participate in a symbiotic relationship with cleaner wrasses. D. americana has been observed visiting cleaner wrasse cleaning stations for periods of time ranging from 1-26 minutes.

Taxonomy

Hildebrandt and Schroeder first described the southern stingray in 1928. The genus Dasyatis of the currently accepted scientific name is derived from the Greek word “dasys” meaning rough or dense and (“b)atus” meaning shark. Synonyms for Dasyatis americana include Trygon pastinaca, Dasyatis scabrata, and Dasibatus hastatus.

Prepared by: Nancy Passarelli and Andrew Piercy