Nurse Shark

Ginglymostoma cirratum

These bottom dwelling sharks are usually yellowish-tan to dark brown and, as adults, average around 7.5 to 8 feet long and over 200 pounds (Rosa et al. 2006). They are nocturnal, scouting the sea bottom for crustaceans, mollusks and stingrays during the night before returning to their preferred cave or crevice where they will often lay together in groups to sleep during the day (Compagno et al. 2005). Nurse sharks are not aggressive, but there are attacks on record, that are usually the result of human provocation (ISAF 2018).

Order – Orectolobiformes

Family – Ginglymostomatidae

Genus – Ginglymostoma

Species – cirratum

Common Names

The term “nurse” probably derived from “Nusse”, the common name originally applied to catsharks of the family Scyliorhinidae, to which G.cirratum was originally thought to belong. In Caribbean waters, the nurse shark is still often referred as “tiburon gato”, or cat-shark (Castro 2000).

Other common names used to refer to this shark include:

carpet shark (English)

cat shark (English)

atlantinpartahai (Finnish)

dormeur (French)

ammenhai (German)

squalo nutrice (Italian)

amerika-tenjikuzame (Japanese)

lixa (Portuguese)

lambaru (Portuguese)

barroso (Portguese)

bañay (Spanish)

con barbillas (Spanish)

gata común (Spanish)

gata manchada (Spanish)

Importance to Humans

Historically, nurse sharks were targetted for their liver oil and for their skin which yields high quality leather (Compagno et al. 1984). At present, there is not a commercial fishery for this species. Regionally, Nurse sharks are still marketed for their fins, meat, and skin, particularly in Panama, Brazil, Venezuela, and the Caribbean. In other areas, nurse sharks are caught and killed by fishermen as they are considered a nuisance animal that takes bait intended for other species. In the Lesser Antilles, where nurse sharks often raid fish traps, they are considered a pest. In the United States commercial fishery, they are often caught as by-catch but are released alive (Rose et al. 2006).

Danger to Humans

Nurse sharks are not generally aggressive and usually swim away when approached. However, some unprovoked attacks on swimmers and divers have been reported. If disturbed, they may bite with a powerful, vice-like grip capable of inflicting serious injury. In some instances, the jaws lock and can only be released using surgical instruments. The frequency of bites has increased in recent years as a result of ecotourism feeding operations (ISAF 2018).

Conservation

IUCN Red List Status: Data Deficient

The IUCN list Nurse Sharks as data deficient. It is not an endangered species; however, its abundance in the littoral waters of Florida has decreased in past decades. The presence of this species in areas with constant anthropogenic activity make it susceptible to disturbance. Because of its relatively docile nature, swimming with, handling, and feeding nurse sharks is popular with ecotourism operators.

In the Eastern Pacific, populations have declined precipitously. In the southern-most ranges of Brazil, the nurse shark is considered locally extinct.

The effects of interactions with humans in coastal waters are unknown, but nursery areas are now limited to remote regions, suggesting an association. Identification and protection of these areas, coupled with further research on the biology of the nurse shark, is needed to provide effective conservation measures (Rosa et al. 2006).

> Check the status of the nurse shark at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

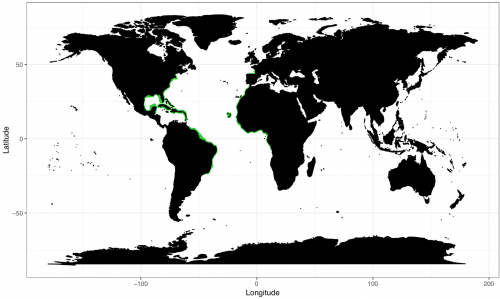

Geographical Distribution

The nurse shark is common in the Atlantic, in the coastal tropical and sub-tropical waters. The Eastern Pacific population has recently been described as a separate species (Ginglymostoma unami). Its distribution ranges from Cape Verde to Gabon, Rhode Island to Southern Brazil (Compagno et al. 2005). Some individuals have been reported in the Gulf of Gascogne in southwest France, as well. This species is locally very common in shallow waters throughout the West Indies, south Florida and the Florida Keys.

Habitat

The nurse shark is a nocturnal animal that rests on sandy bottoms or in shallow-water caves and rock crevices during the day. They occasionally occur in groups of up to 40 individuals, where they can be seen lying close together, sometimes piled upon one another (Compagno et al. 1984). Nurse sharks are active during the night, often swimming near the bottom or clambering across the sea floor, using their muscular pectoral fins as limbs (Compagno et al. 2005). Large juveniles and adults are usually found around deeper reefs and rocky areas at depths of 3-75 meters (10-246 ft) during the daytime moving into shallower waters of less than 20 meters (65 ft) after dark. Juveniles are generally found around shallow coral reefs, grass flats or mangrove islands in 1-4 meters (3-13 ft) of water (Castro 2000). Nurse sharks show a strong preference for specific resting sites, repeatedly returning to the same caves and crevices after nocturnal activity (Compagno 1984).

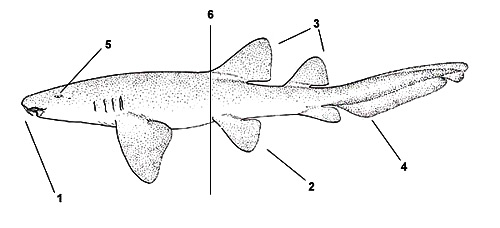

Distinguishing Characteristics

1. Mouth near tip of snout has nasal barbels on either side

2. First and second dorsal and anal fins are broadly rounded

3. The second dorsal fin is slightly smaller than the first

4. There is no distinct lower lobe on the caudal fin

5. Eyes are very small

6. First dorsal fin originates well behind the pectoral fins and over or behind the origin of the pelvic fins

Biology

Distinctive Features

Nurse sharks have two spineless, rounded dorsal fins with the first larger than second, and one anal fin. The origin of the first dorsal fin is over the origin of the pelvic fin. The caudal fin is more than ¼ of the animal’s total length (Compagno et al. 2005).

The sub-terminal mouth is well in front of the eyes, the spiracles are minute, and moderately long barbels reach the mouth (Compagno et al. 2005). Nasoral grooves are present, but there is no perinasal groove.

Coloration

Adult nurse sharks generally range from light tan to dark brown in color. Juveniles up to 55 cm (22 in) have small black spots, with an area of lighter pigmentation surrounding each spot, covering the entire body. These are bands of lighter and darker pigmentation along the dorsal surface. Juveniles (70-120 cm / 28-48 in) are capable of limited color changes. In a tank experiment small nurse sharks, covered for just a few minutes became considerably lighter than individuals exposed to full sunlight (Castro 2000). Unusually pigmented individuals (e.g. brilliant yellow or milky white) have been reported several times.

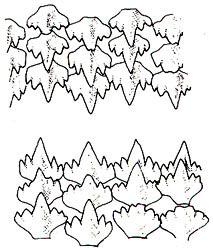

Dentition

Nurse sharks possess an independent dentition, the simplest type of tooth arrangement found in sharks where there is no overlap between teeth. This allows forward movement of replacement teeth that is independent of adjacent teeth in the jaw. (Sharks with imbricate or overlapping dentitions, can only replace teeth when the adjacent “blocking” teeth are also lost). Replacement rates among juveniles are generally faster than for adults. Tooth replacement occurs faster in summer, when water temperatures are higher (Luer et al. 1990).

Size, Age, and Growth

Size at maturity for females is about 230-240 cms and about 210-214 cms for males. Size at birth is in the 27-30 cms (11-12 in) range. Age at maturity for females is 15-20 years and for males 10-15 years. The maximum recorded size of a nurse shark is 308 cm (Rosa et al. 2006).

Food Habits

The nurse shark is a nocturnal predator that feeds mainly on fish, stingrays, mollusks (octopi, squids and clams) and crustaceans. Algae and corals are occasionally found in their stomachs, as well. The nurse shark has a small mouth but its large pharynx allows it to suck in food items efficiently. This system probably allows the species to prey on small fish that are resting at night, but that are too active for the sluggish nurse shark to catch during the day. Heavy-shelled conchs are flipped over, and the snail extracted by use of suction and teeth (Rosa et al. 2006).

Young nurse sharks have been observed resting with their snouts pointed upwards and their bodies supported off the bottom on their pectoral fins. Some suggest this posture may provide a false shelter for crabs and small fishes that the shark can ambush and eat (Compagno et al. 1984).

Reproduction

The nurse shark is an ovoviviparous species. This means that embryonic development occurs in an egg case within the mother’s ovary. The embryo has its own yolk sac, which is absorbed during development, and there is no placental nourishment from the mother. The nurse shark has a biennial reproductive cycle. After mating, gestation takes five to six months (Compagno et al. 2005). The young are born in late spring/early summer with litter of 20-30 pups. Each pup measures 27-30 cm (10.6-11.8 inches) total length (Rosa et al. 2006). It takes another eighteen months for the ovaries to produce enough mature eggs for the next breeding cycle. In the waters of the Florida Keys and the Dry Tortugas archipelagos, the reproductive behavior of the nurse shark has been regularly observed and studied.

Its copulatory behavior is among the best documented among sharks. Males approach females that are resting on the sea floor or are swimming just above it. The male then bites one of the female’s pectoral fins simultaneously pushing, trying to turn her onto one side (Compagno et al. 2005). In this position it is easier for a male to insert his clasper, vigorously bending the lower portion of his body towards the female’s cloaca.

A large number of males generally try to mate with a single female, often leading to females bearing numerous scars and bruises from male bites. Females frequently try to avoid contact with males by swimming in very shallow water, where they can bury their pectoral fins in the sand (Castro 2000).

Predators

There are no species that regularly prey on nurse sharks. However, some larger sharks are known to occasionally feed on them. Remains of nurse sharks have been found in lemon shark and tiger shark stomachs, and attacks on nurse sharks by bull sharks and great hammerhead sharks have been observed (Castro 2000).

Parasites

Nematodes have been observed in the gills of nurse sharks in captivity at the New York Aquarium, U.S.

Taxonomy

The nurse shark was first described by Bonnaterre (1788), as Squalus cirratus. The current scientific combination, Ginglymostoma cirratum was first assigned by Muller and Henle in 1841. Gynglymostoma is derived from the Greek words “gynglimos” = hinge and “stoma” = mouth. The species name cirratum is translated from Latin as curl. Synonyms used to refer to this species in past scientific literature are Squalus punctulatus Lacepède 1800, Squalus punctatus Bloch & Schneider 1801, Squalus argus Bancroft 1832, Ginglymostoma fulvum Poey 1861, and Ginglymostoma caboverdianus Capello 1867.

Similarities in the reproductive cycle and molecular phylogenetic data indicate a close relationship between the nurse shark family Ginglymostomatidae and the whale shark family Rhincodontidae.

References

Castro, J. (2000). The biology of the nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum, off the Florida east coast and the Bahama Islands. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 58/1: 1-22.

Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). FAO species catalogue. Vol. 4. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125, Volume 4, Part 1.

Compagno, L., Dando, M., & Fowler, S. (2005). A Field Guide to the Sharks of the World. London: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

Luer, C., Blum, P., & Gilbert, P. (1990). Rate of Tooth Replacement in the Nurse Shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum. Copeia, 1990(1), 182-191. doi:10.2307/1445834

Rosa, R.S., Castro, A.L.F., Furtado, M., Monzini, J. & Grubbs, R.D. (2006). Ginglymostoma cirratum. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2006: e.T60223A12325895. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2006.RLTS.T60223A12325895.en.

Revised by Lindsay French, Jennifer Dorrian and Gavin Naylor 2018