Cookiecutter Shark

Isistius brasiliensis

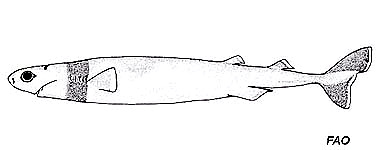

This small, cigar-shaped shark is dark brown on top and light on the underside, with a darker band around its neck. The light underside glows, attracting fish, whales, and sharks. It attaches itself to the prey and uses its serrated bottom teeth to cut out a perfectly circular chunk of flesh. It has small fins to the rear of its body, and large green eyes. Because of its size and deep water habits, it is considered harmless to humans. It can be considered a parasite due to its nature to feed on larger animals without killing them (Papastamatiou et al. 2010).

Order – Squaliformes

Family – Dalatiidae

Genus – Isistius

Species – brasiliensis

Common Names

The cookiecutter shark is named after the cookie-shaped wounds that it leaves on the bodies of its prey items.

English:

- Cookie-cutter shark

- Cigar shark

- Luminous shark.

Other Common Names:

- Danish almindelig cookiecutterhaj

- Dutch koekjessnijder

- Finnish brasilianvalohai

- French squalelet féroce

- German kleiner leuchthai

- Japanese darumazame

- Portuguese cação luminoso

- Spanish tiburón cigarro, tollo cigarro, tiburón puro

Importance to Humans

Although cookiecutter sharks prey upon commercially caught fishes, the damage is of little consequence. It is often considered a nuisance due to damage done to submarines. Due to their small size and deepwater habitat, they are of no commercial importance (Stevens. 2003).

Danger to Humans

According to the International Shark Attack File, the cookie cutter shark has been involved in four confirmed, unprovoked bites, all of which occurred in Hawaii. It is considered harmless to people due to its deep-water habitat as well as its small size (International Shark Attack File 2018).

Conservation

The cookiecutter shark lives in the depths of the ocean, making it a difficult species for a targeted fishery. However, cookiecutter sharks are sometimes caught during the nighttime hours when they migrate vertically in search of prey. In the future, this shark may suffer reduced population levels if fishing pressures are allowed to increase. There are currently no conservative measures being taken to preserve the cookie cutter shark (Stevens. 2003).

> Check the status of the cookiecutter shark at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

Geographical Distribution

This small shark is found in the western Atlantic Ocean from the Bahamas south to the coast of southern Brazil. In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, it is found from Cape Verde, Guinea to Sierra Leone, southern Angola and South Africa including Ascension Island. The cookiecutter shark also lives in the waters of the Indo-Pacific from Mauritius to New Guinea, Lord Howe Island, and New Zealand north to Japan and east to the Hawaiian Islands. It is found off Easter Island and the Galapagos in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Records of cookiecutter sharks off Australia include the waters off Queensland, New South Wales, Tasmania, and Western Australia (Stevens. 2003).

Habitat

Found in deep water at depths below 3,281 feet (1000 m) during the day, cookiecutter sharks migrate vertically to surface waters at night to feed (Stevens. 2003).

Biology

Distinctive Features

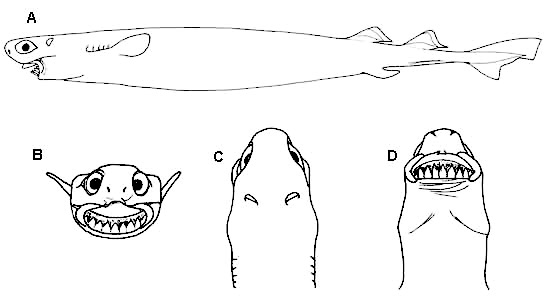

The cookiecutter shark has a small cigar-shaped body with a short conical snout and unique suctorial lips. The eyes are located toward the front of the head, but far enough back that the shark lacks much of a binocular field of vision (Klimley. 2013). There are two close-set spineless dorsal fins of equal size positioned toward the rear of the body. The pelvic fins are larger in size than the dorsal fins; the pectoral fins are subquadrate in shape. The caudal fin is large with a long ventral lobe. The anal fin is absent on this species (Compagno. 2005).

Isistius plutodus is a similar species to the cookiecutter shark, however, I. plutodus has fewer and larger teeth and lacks the dark-colored collar as well as the dark tips on the caudal fin. Also, the base of the second dorsal fin is over twice as long as the base of the first dorsal fin of I. plutodus (Stevens. 2003).

Coloration

The dorsal portion of the cookiecutter shark is dark brown with a lighter ventral surface. There is a distinct dark brown collar around the gill region. The entire ventral surface of the cookiecutter shark with the exception of the dark collar contains a network of tiny light-producing organs called photophores (Klimley. 2013). Photophores produce an even greenish colored glow on the underside of this shark. These photophores reportedly produce light for up to three hours after the death of the shark. The fins have pale margins with the exception of the caudal fin which has dark tips (Compagno. 2005).

Dentition

Cookiecutter sharks have 30-37 small, erect teeth in the upper jaw and 25-31 larger triangular teeth in the lower jaw with larger specimens having the larger numbers. The teeth are interconnected at the bases, allowing the entire row of teeth to move if one tooth is touched (Compagno. 2005). The teeth are lost as a complete unit rather than individual teeth common to most sharks. As the lower teeth are shed, they are ingested by the shark. This is thought to aid in maintaining the calcium levels in the body (Klimley. 2013).

Dermal Denticles

The denticles are roughly square-shaped with a depression in the middle and raised points at the corners (Compagno. 2005).

Size, Age & Growth

Male cookiecutter sharks grow to a maximum of 16.5 inches (42 cm) total length (TL) while females reach 22 inches (56 cm) TL. Males mature at approximately 14 inches (35.6 cm) in length and the females are mature at 16 inches (40.6 cm) in length (Compagno. 2005).

Food Habits

The cookiecutter shark has a unique feeding method. Prey items are attracted to the ventral surface of the cookiecutter shark due to the light given off by the glowing photophores (Compagno. 2005). The glowing area appears similar to a small fish from the depths, prompting larger fish to approach in search of their next meal. Just prior to biting the cookiecutter shark, the large fish is unexpectedly bitten by the shark. The cookiecutter shark attaches itself to its prey with its sucking lips and sharp pointy upper teeth. Once it is attached, the small shark spins its body removing a cookie-shaped plug from the flesh of its prey with its larger serrated bottom teeth. The prey is left with a perfectly round cookie cutter-shaped hole in the side of its body (Compagno. 2005). Common prey items include large fishes such as marlin, wahoo, dolphin, tuna, sharks, and stingrays as well as marine mammals including seals, whales, and dolphins. There are reports of this shark leaving crater marks on the sonar domes of nuclear submarines. The cookiecutter shark has also been reported to commonly feed on whole squid and crustaceans (Papastamatiou et al. 2010).

Reproduction

The cookiecutter shark is ovoviviparous, meaning it gives birth to live pups after they develop inside egg cases within the uterus of the mother. Each developing pup feeds off the yolk inside the egg case, remaining there until it is fully developed. Then it is hatched out from the egg, followed shortly after by the mother giving live birth to the fully developed pups. There are 6-12 live young born per litter (Compagno. 2005). Although little is known about the reproduction of cookiecutter sharks, it is believed that oceanic islands may provide a nursery habitat for this species (Stevens. 2003).

Predators

Potential predators of the cookiecutter shark include large sharks and bony fish (Compagno. 2005).

Taxonomy

This small shark was originally described by Quoy & Gaimard in 1824 as Tristius brasiliensis. This name was later changed to Scymnus brasiliensis, followed by the currently valid Isistius brasiliensis (Quoy & Gaimard, 1824). The genus name Isistius is derived from Isis, the Egyptian goddess of light; the species name brasiliensis refers to its presence in the waters off the coast of Brazil. Synonyms in past scientific literature include Scymnus brasiliensis torquatus Müller & Henle 1839, Scymnus unicolor Müller & Henle 1839, Scymnus brasiliensis unicolor Müller & Henle 1839, Scymnus torquatus Müller & Henle 1839, Squalus fulgens Bennett 1840, and Leius ferox Kner 1864.

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester

Revised by: Tyler Bowling 2019

References:

- Compagno, Leonard, et al. A Field Guide to the Sharks of the World. Collins, 2005.

- Klimley, A. Peter. The Biology of Sharks and Rays. The University of Chicago Press, 2013.

- Papastamatiou, Yannis P., et al. “Foraging Ecology of Cookiecutter Sharks (Isistius Brasiliensis) on Pelagic Fishes in Hawaii, Inferred from Prey Bite Wounds.” Environmental Biology of Fishes, vol. 88, no. 4, 2010, pp. 361–368., doi:10.1007/s10641-010-9649-2.

- Stevens, J. (SSG Australia & Oceania Regional Workshop, March 2003). 2003. Isistius brasiliensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2003: e.T41830A10575586.