King Mackerel

Scomberomorus cavalla

This elongated torpedo-shaped fish usually folds its first dorsal fin and pectoral fins into grooves, and keeps its second dorsal fin, anal fin, and finlets up to help with speed and maneuvering. It has a pointed snout and a distinctly forked caudal (tail) fin, and is usually silvery white with an iridescent black dorsal surface. They prefer warmer coastal waters where they feed on smaller schooling fish and grow to between 20 and 35 inches long. They are a popular game fish, but are also one of the four fish at the top of the FDA’s danger list of mercury poisoning when eaten.

Order – Perciformes

Family – Scombridae

Genus – Scomberomorus

Species – cavalla

Common Names

King mackerel (English), kingfish (English), carite (Spanish), carite lucio (Spanish), carite sierra (Spanish), carito (Spanish), carito lucio (Portuguese), cavala (Portuguese), cavala impigem (Portuguese), cavala verdadeira (Portuguese), kongemakrell (Norwegian), konigsmakrele (German), korolevskaya makrel (Russian), kungsmakrill (Swedish), kuningasmakrilli (Finnish), makrela kawala (Polish), maquereau (French), oo-sawara (Japanese), peto (Spanish), rey (Spanish), sawara (Japanese), serra real (Portuguese), serrucho (Spanish), sierra (Spanish), sgombro reale (Italian), taza blan (Creole), and thazard barre (French).

Importance to Humans

The king mackerel is the most important game fish within the genus Scomberomorus, with fishing seasons open April through December off North Carolina and year-round in Florida waters. Recreational catches from U.S. waters are 2-10 times larger than commercial catches. There are commercial fisheries located off Louisiana, Florida, and North Carolina. Fishing gear includes hook and line using live bait or trolled lures, and gill nets. The fish is sold as steaks, fresh, canned, or salted.

Danger to Humans

There have been some reports of ciguatera poisoning. Ciguatera poisoning occurs when humans eat a fish that has eaten a toxin produced by the dinoflagellate, Gambierdiscus toxicus. Coral grazers ingest this toxin, passing it up through the food web to piscivorous fish and finally to humans. The symptoms of ciguatera poisoning may last as long as weeks or months, beginning with gastrointestinal symptoms within hours of consumption, followed by neurological and cardiovascular symptoms.

Conservation

The king mackerel is not listed as endangered or vulnerable with the World Conservation Union (IUCN). The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Check the status of the king mackerel at the IUCN website.

Geographical Distribution

The king mackerel is found along the western coast of the Atlantic Ocean from Massachusetts to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and the Gulf of Mexico. The Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico stocks mix in south Florida waters.

Habitat

The king mackerel prefers outer reefs and coastal waters. Resident populations are found in northeastern Brazil, Louisiana, and south Florida waters. King mackerels occur in depths between 75.5 – 111.5 feet (23 – 34 m). Dependent upon warm temperatures, king mackerel can migrate along the east coast of the U.S. The Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic populations migrate separately, with the division lines being in Volusia-Flagler counties of southeast Florida in November through March and in Monroe-Collier counties of southwest Florida during April through October.

Biology

Distinctive Features

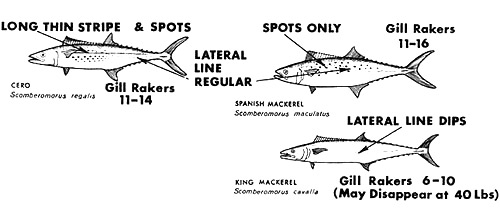

Unlike other members of Scomberomorus, the king mackerel lacks a black area on the anterior portion of the first dorsal fin. The king mackerel has 12-18 spines in its first dorsal fin; 15-18 rays in the second dorsal fin, which are followed by 7-10 finlets; and 21-23 pectoral fin rays. Its body is about five times the size of its head, and about six times as long as it is deep. The entire body is covered with rudimentary scales, except for its pectoral fin. The lateral line drops sharply after the second dorsal fin, and then continues on to the tail, distinguishing it from the cero mackerel (Scomberomorus regalis). The king mackerel also lacks scales on the pectoral fins as does the Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus maculatus), in contrast to the cero mackerel which has scales extending onto the pectoral fin.

Coloration

The king mackerel is a silver fish with indistinct bars or spots on its side. The dorsal surface is black with iridescent tones of blue and green. Young fish have small bronze spots in 5 or 6 irregular rows.

Dentition

King mackerel have 30 triangular teeth aligned closely together.

Size, Age, and Growth

The largest species of mackerel in the Atlantic, the king mackerel grows to 19.7-35.4 inches (50-90 cm) in length. The maximum size reported of the king mackerel is 72.4 inches (184 cm) and 99 pounds (45 kg). Maximum age recorded is 14 years for females and 11 years for males. However, in another study, fish much older were recorded. Females living for up to 26 years and males for up to 24 years were documented. In this study, which took place from 1986-1992 in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, fish over the age of 20 years were rare. Only 0.28% of females and 0.30% of males caught were over 20 years of age.

Food Habits

Like other members of this genus, king mackerel feed primarily on fishes. They prefer to feed on schooling fish, but also eat crustaceans and occasionally mollusks. Some of the fish they eat include jack mackerels, snappers, grunts, and halfbeaks. They also eat penaeid shrimp and squid. Adult king mackerels mainly eat fish between the sizes of 3.9-5.9 inches (100-150 mm). Juveniles eat small fish and invertebrates, especially anchovies. The Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico populations differ significantly in their feeding habits. The Atlantic stock ate 58% engraulids, 1% clupeids, and 3.1% squid, the Gulf stock consumed 21.4% engraulids, 4.3% clupeids, and 7.1% squid. The Gulf population also showed more diversity in its feeding habits. In south Florida, the king mackerel’s food of choice is the ballyhoo. On the east coast of Florida, the king mackerel prefers Spanish sardines, anchovies, mullet, flying fish, drums, and jacks.

Reproduction

Little is known about the reproduction of king mackerel. Spawning occurs most frequently during May through September. Eggs are believed to be released and fertilized continuously during these months, with a peak between late May and early July with another between late July and early August. The ovaries of the king mackerel have five stages of development. Maturity may first occur when the females are as small as 17.7-19.6 inches (450-499 mm) in length and usually occurs by the time they are 35.4 inches (800 mm) in length. Stage five ovaries, which are the most mature, are found in females by about age 4 years. Males are usually sexually mature at age 3, at a length of 28.3 inches (718 mm). Females in U.S. waters, between the sizes of 17.6-58.6 inches (446-1,489 mm) released 69,000-12,200,000 eggs. Because both the Atlantic and Gulf populations spawn while in the northernmost part of their ranges, there is some thought that they are reproductively isolated groups.

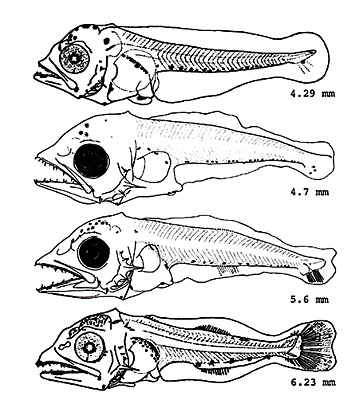

Larvae of the king mackerel have been found in waters with temperatures between 79-88°F (26-31°C). This stage of development does not last very long. Larva of the king mackerel can grow up to 0.02 to 0.05 inches (0.54-1.33 mm) per day. This shortened larval stage decreases the vulnerability of the larva, and is related to the increased metabolism of this fast-swimming species. The larvae can be identified by their large, wide open jaws, well-developed teeth, large eyes, and a pointed snout. The coloration of the brain develops early and retains the color throughout life. The color of the trunk develops at about 0.8 inches (20 mm). The fins remain unpigmented until the fish reaches 1.2 inches (31 mm) in length, with the caudal fin remaining unpigmented.

Predators

Larval and juvenile king mackerel fall prey to little tunny and dolphins. Adult king mackerel are consumed by pelagic sharks, little tunny, and dolphins. Bottle-nosed dolphins have been known to steal king mackerel from commercial fishing nets. Young king mackerel often accidentally get caught in shrimping nets.

Parasites

The king mackerel is a host to 23 parasitic species. The copepods Caligus bonito, Caligus mutabilis, and Caligus productus are found on the body surface and on the wall of the branchial cavities. Other copepods including Brachiella thynni, located on the fins, and Pseudocycnoides buccata, found on the gill filaments, are also parasites of the king mackerel.

Other parasites include digenea (flukes), monogenea (gillworms), cestoda (tapeworms), nematoda (roundworms), acanthocephala (spiny-headed worms), copepods, and isopods. Sea lampreys (Petromyzon marinus) is an ectoparasite associated with the king mackerel.

Taxonomy

The king mackerel was first described by Cuvier in 1829. The genus Scomberomorus is derived from the Latin word “scomber” = mackerel and the Greek word “moros” = silly, stupid. The species cavalla originates from the Latin word “caballa” meaning horse. King mackerel has appeared in literature under a variety of names. Although these synonyms are no longer valid, they include Cybium acervum Cuvier 1832, Cybium caballa Cuvier 1832, Cybium immaculatum Cuvier 1832, and Scomberomorus caballa Cuvier 1832.

Prepared by: Tina Perrotta