Dawn Mitchell | PCP PIRE Project Assistant

PCP PIRE Principal Investigator Carlos Jaramillo, PCP PIRE affiliate Camilo Montes and colleagues published a groundbreaking paper in Science this month that challenges previous thought on the date of the closure of the Central American Seaway. The study, with Montes as first author, found that the Isthmus of Panama must have had a land connection with South America by the Middle Miocene, 13-15 million years ago instead of the widely held date of 3 million years ago.

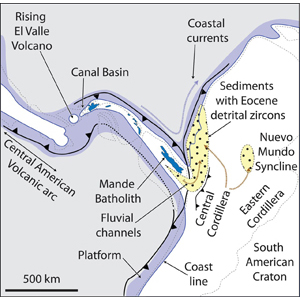

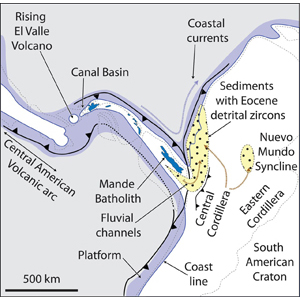

The team came to this conclusion because detrital zircons of Eocene age were found in middle Miocene fluvial and shallow marine sediments of northwestern South America. A large part of the Panama arc formed from the latest Cretaceous to the Eocene, with magmatic activity occurring again in some parts as late as 19 Ma and 10 Ma. Northwestern South America, on the other hand, was formed from the accretion of rocks ranging from late Precambrian to Cretaceous in age. The presence of Eocene detrital zircons in fluvial and shallow marine sediments of northwestern South America during the middle Miocene and the absence of such zircons in Oligocene and early Miocene sediments suggest that some part of the Panama arc had docked to South America, allowing rivers originating in Panama to flow into northern South America. This docking would also mean that the Central American Seaway had already closed, and events that occur 10 million years later such as the Great American Biotic Interchange may have a more complex history than originally thought.

Another paper published this month by Christine Bacon and colleagues (including PCP PIRE’s Carlos Jaramillo and Alexandre Antonelli) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences supports an early rise of the isthmus and a complex history of dispersal between the North and South American landmasses. Fossil data shows an increasing number of migration events from 10 million years ago onwards, with a drastic increase in North American taxa migrating to South America at around 3 million years ago. Molecular genetic data indicates that the migration of plant and animal species across the isthmus might have happened in multiple episodes rather than one large migration. Major changes in the rate of migration occurred at 23 million years ago and within the last 10 million years, and the number of migrants during a particular time may be related to dropping global temperatures that led to glaciation and vegetation changes in the northern hemisphere as well as a drop in global sea levels.

New findings are continuously coming out of Panama through the work of PCP PIRE researchers and others, as the geology of Panama continues to reveal its dynamic secrets.

References:

Montes, C., Cardona, A., Jaramillo, C., Pardo, A., Silva, J. C., Valencia, V., Ayala, C., Pérez-Angel, L. C., Rodriguez-Parra, L. A., Ramirez, V., Niño, H. 2015. Middle Miocene closure of the Central American Seaway. Science 348 (6231), 226-229. DOI:10.1126/science.aaa2815.

Bacon, C. D., Silvestro, D., Jaramillo, C., Tilston Smith, B. T., Chakrabarty, P., Antonelli, A. 2015. Biological evidence supports an early and complex emergence of the Isthmus of Panama. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published ahead of print. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423853112.

Dawn Mitchell | Asistente del Proyecto PCP PIRE

Los miembros del PCP PIRE, Carlos Jaramillo (investigador principal), Camilo Montes y colegas, publicaron este mes en Science un artículo pionero que desafía el pensamiento anterior sobre la fecha del cierre de la Vía Marítima Centroamericana. El estudio, con Montes como primer autor, encontró que el Istmo de Panamá debe haber tenido una conexión terrestre con América del Sur hacia el Mioceno medio, es decir hace 13-15 millones años, en lugar de la fecha ampliamente sostenida de hace 3 millones de años.

El equipo llegó a esta conclusión porque se encontraron circones detríticos de edad Eoceno en sedimentos fluviales y marinos del Mioceno medio del noroeste de América del Sur. Una gran parte del arco de Panamá se formó desde el Cretácico tardío hasta el Eoceno, con actividad magmática recurrente en algunas partes tan tarde como entre 19 y 10 millones de años. El noroeste de América del Sur, por su parte, se formó a partir de la acumulación de rocas desde finales del Precámbrico hasta el Cretácico. La presencia de circones detríticos del Eoceno en sedimentos marinos someros y fluviales del noroeste de América del Sur durante el Mioceno medio y la ausencia de este tipo de circones en sedimentos del Oligoceno y el Mioceno temprano sugieren que una parte del arco Panamá se había acoplado a América del Sur, permitiendo que ríos que nacían en Panamá fluyeran hacia el norte de América del Sur. Este acoplamiento también significaría que la vía marítima centroamericana ya se había cerrado y que los acontecimientos que se produjeron 10 millones de años más tarde, como el Gran Intercambio Biótico Americano, podrían tener una historia más compleja de lo que se pensaba originalmente.

Otro artículo publicado este mes por Christine Bacon y colegas (incluyendo los miembros del PCP PIRE Carlos Jaramillo y Alexandre Antonelli) en la revista Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences apoya un levantamiento temprano del istmo de Panamá y una compleja historia de dispersión entre las masas continentales de América del Norte y del Sur. Datos fósiles muestran un creciente número de eventos de migración a partir de 10 millones de años en adelante, con un aumento drástico de taxones de América del Norte migrando hacia América del Sur hace alrededor de 3 millones de años. Datos de genética molecular indican que la migración de especies de plantas y animales a través del istmo podría haber sucedido en múltiples episodios en lugar de una migración grande. Grandes cambios en las tasas de migración se produjeron hace 23 millones de años y en los últimos 10 millones de años, mientras que el número de migrantes en un momento determinado podría estar relacionado con la caída en las temperaturas globales que condujeron a glaciaciones y cambios en la vegetación en el hemisferio norte, así como una caída en los niveles globales del mar.

Nuevos hallazgos en Panamá vienen haciéndose públicos continuamente a través de la labor de los investigadores del PIRE PCP y colegas. La geología de Panamá sigue revelando sus dinámicos secretos.

Referencias:

Montes, C., Cardona, A., Jaramillo, C., Pardo, A., Silva, J. C., Valencia, V., Ayala, C., Pérez-Angel, L. C., Rodriguez-Parra, L. A., Ramirez, V., Niño, H. 2015. Middle Miocene closure of the Central American Seaway. Science 348 (6231), 226-229. DOI:10.1126/science.aaa2815.

Bacon, C. D., Silvestro, D., Jaramillo, C., Tilston Smith, B. T., Chakrabarty, P., Antonelli, A. 2015. Biological evidence supports an early and complex emergence of the Isthmus of Panama. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published ahead of print. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423853112.