Harmful plants have evolved to protect themselves from predators

It’s one of society’s hotly debated questions: ketchup or mustard?

For some, the harsh, acidic flavor of mustard is too much to handle on a hot dog or burger, but Florida Museum of Natural History botanist Doug Soltis is a fan of the yellow condiment and the science behind its flavors.

“Every time you put mustard on your hot dog, you should be thinking of plants and defense,” said Soltis, a University of Florida distinguished professor. “The mustard family has evolved that chemical pathway to produce those mustard oil compounds to make what is essentially a ‘mustard bomb.’ ”

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Mustard plants developed their pungent profile to protect themselves from being consumed by other creatures through years of evolutionary changes, he said.

And they are not alone – many plants are well-known for their smelly, poisonous or dangerous qualities, some of which are highlighted in the Florida Museum’s current featured exhibit, “Wicked Plants,” on display through Jan. 15, 2017.

Based on Amy Stewart’s book, “Wicked Plants: The Weed That Killed Lincoln’s Mother and Other Botanical Atrocities,” the exhibit features more than 100 of the world’s most diabolical botanicals.

But Soltis said their sometimes tragic results are not intended by plants.

“This is nothing personal at all against our species,” Soltis said. “The reason for this is that unlike most vertebrates, which can flee when they are a prey item, plants can’t do that. They’re stationary.”

For about 450 million years, plants and their predators have been trapped in an ‘arms race’ of evolution. First, the plants are attacked by something such as an animal that consumes their leaves; in response, future plant generations alter their chemistry or characteristics to defend themselves and the cycle continues as each species evolves to outsmart the next.

“Plants have been so inventive in terms of what they come up with in order to survive,” said Pam Soltis, also a UF distinguished professor and Florida Museum curator of molecular systematics and evolutionary genetics. “Some types of chemical compounds can be completely non-effective on humans, or they can be very poisonous to us as well.”

One of the best known stories about poisonous plants goes back thousands of years. Ancient Greeks used poison hemlock as a means of execution, and one of history’s most famous victims is the philosopher Socrates.

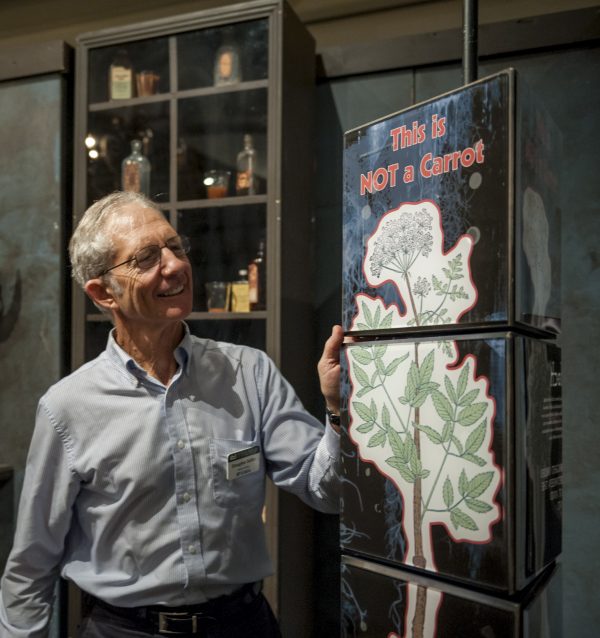

But even today, poison hemlock is a plant you might accidentally encounter. Poison hemlock and carrots share a recent common ancestor and have a similar appearance. Doug Soltis recalled a time he struck up a conversation with a man sitting next to him on a plane whose parents had died when they started foraging in a meadow for food during a rafting trip in a remote area.

“They started eating what they thought were wild carrots, and it was poison hemlock,” he said.

Poison hemlock is native to Florida, but other poisonous plants were intentionally brought to the Sunshine State.

Oleander is a beautiful non-native flowering shrub that is planted in many areas as an ornamental. However, beyond its lovely exterior, its seeds, flowers and sap are all poisonous.

“Even in the areas they grow, oleander produces so much toxin that if it’s near a little body of water, the toxin can even seep into the water, making it not very good to drink,” Doug Soltis said.

Some plants, such as philodendrons, have other ways of building up their strength to withstand predators.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

“They protect themselves by producing tiny crystals in their cells, if you can imagine, so eating them is like chewing glass,” Doug Soltis said. “Some of their relatives are called dumb cane, not because the plant is dumb, but because once the crystals get embedded in your mouth, you can’t speak.”

Some poisonous plants seem to use mimicry for protection–taking on characteristics of similar plants that are not poisonous. This can happen because the plants are somewhat related, as in the case of poison hemlock and carrots, but others may not be related at all.

“Camas lily produces big bulbs that are good sources of starch,” Pam Soltis said, referring to a plant that grows primarily in the Western United States. “Native Americans used these bulbs for food, then when the European settlers came, they also used them.”

“But there’s another thing that looks just like it,” she said. “Until it flowers.”

When the camas lily flowers, it produces bright purple flowers; its evil twin, dubbed death camas, produces yellow or white flowers. Although it is also good source of starch, death camas lives up to its name.

Some of these dangerous plants continue to thrive so close to us because they are beautiful, but often plants have substantial medicinal capabilities.

“Over the course of the last few centuries, we’ve learned a lot more about uses of plants and particular plant properties that can be modified to develop pharmaceuticals,” Pam Soltis said.

One example is digitalis, commonly known as foxglove. The use of digitalin extracted from the plants for the treatment of heart failure has been traced back to 10th century Europe according to peer-reviewed journal studies and other medical literature.

Pam Soltis said although plants may seem wicked or scary to some, she would rather use the word ‘tricky’ to describe them.

“There’s a lot more to them than meets the eye, both in terms of benefit and harm,” she said. “A lot of the chemistry they’ve developed to protect themselves in sort of a wicked way becomes beneficial for humans, too.”

Learn more about the Herbarium at the Florida Museum.

Learn more about the Laboratory of Molecular Systematics & Evolutionary Genetics at the Florida Museum.