Smilodon fatalis

Quick Facts

Common Names: saber-tooth cat (or sabertooth cat), sabercat

Smilodon fatalis had a body mass ranging from 350 to 600 pounds, similar in weight to the modern Siberian tiger.

Fossils of Smilodon fatalis are not particularly common in Florida, but there have been many fossils found across the United States, including a prolific collection in Rancho la Brea in Los Angeles, California.

Age Range

- Late middle to latest Pleistocene Epoch; late Irvingtonian and Rancholabrean land mammal ages

- About 700,000 to 11,000 years ago

Scientific Name and Classification

Smilodon fatalis Leidy, 1868

Source of Species Name: not stated in Leidy’s original description, but from the Latin word fatalis, meaning of fate or destiny. But presumably Leidy’s intent was based on the standard English usage of the word ‘fatal’, meaning deadly or causing death.

Classification: Mammalia, Eutheria, Laurasiatheria, Carnivora, Feliformia, Aeluroidea, Felidae, Machairodontinae, Smilodontini

Alternate Species Names: Machairodus floridanus, Smilodon californicus, Smilodon floridanus

Overall Geographic Range

Smilodon fatalis lived in southern and central North America, Central America, and western South America (Kurten and Werdelin, 1990). The type locality is in southeastern Texas (Leidy, 1868).

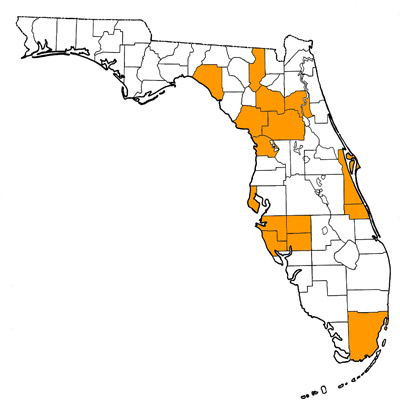

Florida Fossil Occurrences

Florida fossil sites with Smilodon fatalis:

- Alachua County—Arredondo 1; Haile 7A

- Brevard County—Melbourne

- Citrus County—Bone Cave; Sabertooth Cave (=Lecanto Cave)

- Columbia County—Ichetucknee River; Santa Fe River

- Dade County—Cutler Hammock

- De Soto County—Peace River 2

- Hardee County—Peace River 11

- Indian River County—Vero Canal Site

- Levy County—Waccasassa River 2; Waccasassa River 6

- Manatee County—Bradenton 51st Street

- Marion County—Reddick 1B; “Rock Crevice” of Leidy (1889b); Withlacoochee River

- Pinellas County—Millennium Park; Seminole Field

- Putnam County—St. Johns Lock

- Sarasota County—Venice area; Warm Mineral Springs

- Taylor County—Aucilla River 1A

Discussion

The genus Smilodon contains three widely recognized species: Smilodon populator, Smilodon fatalis, and Smilodon gracilis (Kurten and Werdelin, 1990; Turner, 1996). Two species names widely used in the older scientific and semi-popular literature, Smilodon californicus and Smilodon floridanus, are almost always now regarded as junior synonyms of Smilodon fatalis. Berta (1985) proposed that Smilodon populator and Smilodon fatalis were actually a single species, with the former name having priority. This approach has been followed in a few other studies, but today most experts on extinct felids regard the two species as distinct. Smilodon populator in this scenario is limited to portions of South America east of the Andes.

Although Smilodon fatalis is known from late Irvingtonian (middle Pleistocene) sites in South Carolina, Arkansas, and Nebraska, fossil localities of this age in Florida have not recorded it (although only three such sites are known, so this absence might be an artifact of the sparse record from this time interval). Thus all known Florida records of the species are from the Rancholabrean land mammal age. Fossils of Smilodon fatalis are not particularly common in Florida. Most records are isolated teeth or bones, typically less than five specimens per locality, and most often just one. A partial skeleton of a subadult individual was found at Arredondo 1 in a limestone quarry southwest of Gainesville in the early 1950s (Fig. 2; Kurten, 1965). According to Kurt Auffenberg (pers. comm. to R. Hulbert), his father and former museum curator Walter Auffenberg told him that this skeleton originally included a skull, but that it was retained by the collector. Its whereabouts are unknown. The best skull of Smilodon fatalis from Florida in a museum collection is still the first specimen ever found, in 1888 at a fissure deposit in a limestone quarry near Ocala (Figs. 3-4; Leidy, 1889a, 1889b). According to Leidy (1889b), this skull originally had some teeth, but they were removed by the person who found it. This specimen is the holotype of Smilodon floridanus and is on public display at the Wagner Free Institute of Science in Philadelphia just where Joseph Leidy himself placed it. It has a nearly complete braincase and most of the right maxilla.

Fossils of Smilodon fatalis can easily be distinguished from those of Smilodon gracilis, the only other species in the genus known from Florida, by their much larger size. According to Christiansen and Harris (2005), Smilodon fatalis had a body mass ranging from 350 to 600 pounds (160 to 280 kg), similar in weights observed in the modern Siberian tiger. In contrast, Smilodon gracilis was only about the size of a modern jaguar, weighing between 120 and 220 pounds (55 to 100 kg). There are also morphologic differences. In the teeth, the upper canine of Smilodon fatalis is more curved and has better developed serrations. The lower third premolar of Smilodon fatalis is usually absent, or if present more vestigial than that of Smilodon gracilis. The inner cusp on the upper fourth premolar, the protocone, is very reduced or even absent in Smilodon fatalis. The only felid of similar (or even larger) size present in the late Pleistocene of Florida is the American lion, Panthera atrox. It too is a relatively rare species in Florida. Almost every bone in the skeleton of these two great cats can be distinguished, as detailed in the classic monograph of Merriam and Stock (1932).

In stark contrast to its rarity in the Florida fossil record is the massive number of well-preserved specimens of Smilodon fatalis at the Rancho la Brea in Los Angeles, California. Over 2,000 skulls alone have been found in the various tar pits there. Naturally it is this tremendous sample that has been most studied by paleontologists, who have used it to analyze almost every imaginable aspect of the paleobiology of this famous species. Among the most studied features are how it captured and killed its prey (e.g., Akersten, 1985, 2005; Anyonge, 1996; McHenry et al., 2007; Meachen-Samuels, 2012), diet and chewing mechanics (e.g., Van Valkenburgh et al., 1990; Biknevicius et al., 1996; Kohn et al., 2005; Wroe et al., 2005; Binder, and Van Valkenburgh, 2010; DeSantis et al., 2012), degree of sociality and sexual dimorphism (e.g., Van Valkenburgh and Sacco, 2002; Carbone et al., 2009; Kiffner, 2009; Van Valkenburgh et al., 2009; Meachen-Samuels and Binder, 2010; Christiansen and Harris, 2012), and growth rates and patterns (e.g., Feranec, 2004; Meachen-Samuels and Binder, 2010; Christiansen, 2012).

Sources

- Original Author(s): Richard C. Hulbert Jr.

- Original Completion Date: April 23, 2013

- Editor(s) Name(s): Richard C. Hulbert Jr. and Natali Valdes

- Last Updated On: December 16, 2020

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida