Atlantic Stingray

Dasyatis sabina

These smaller stingrays grow to around 12 to 14 inches wide, and are brown to yellowish-brown on tip, and whitish underneath. They are oval with long, pointed snouts, appearing almost spade-shaped. They have long venomous spines on their tails, but they are not aggressive, so must human interaction is from surprising or threatening a stingray. These Atlantic stingrays can survive in brackish or fresh water, so they can be found in lakes, rivers, and estuaries.

Order: Myliobatiformes

Family: Dasyatidae

Genus: Dasyatis

Species: sabina

Common Names

Atlantic stingray (English), atlantinkeihasrausku (Finnish), Atlantische pijlstaartrog (Dutch), floridskiy khostokol (Russian), raie (French), raya enana (Spanish), and raya hocicona (Spanish).

Importance to Humans

Research is being conducted by the biomedical and neurobiological industries on the venomous component of the tail spine and its possible future applications in those fields.

Danger to Humans

Stingrays do not attack people, however if it is stepped on, the stingray will utilize its spine as a form of defense. Although being pierced by the stingray’s spine is painful, it is rarely life threatening to humans.

Conservation

> Check the status of the Atlantic stingray at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

However, localized freshwater populations of this species have shown decline in health and reproduction due to water quality issues including algae blooms, storm water runoff, and wastewater discharge.

Geographical Distribution

The Atlantic stingray is a coastal resident of the western North Atlantic Ocean. It ranges from Chesapeake Bay south to Florida, and in the Gulf of Mexico south to Campeche, Mexico.

Habitat

This stingray prefers warm coastal and estuarine waters above 59° F (15° C) and can endure temperatures above 86° F (30° C). Temperature induced seasonal migrations have been observed throughout its range. The Atlantic stingray is found in the Chesapeake Bay, its northernmost range, during the summer and fall when the water temperature is warmest. Between October and November it moves south to warmer waters. In other areas, rays migrate from shallow to deeper waters where the water is above 59° F (15° C) during the winter months.

While inshore, the Atlantic stingray generally occurs in shallow waters at depths of 6.5-20 feet (2-6m). During its seasonal offshore migration, it is rarely located in water deeper than 80 feet (25m). This fish prefers habitats with a sand or silt/sand seabed, which allows the stingray to bury itself to hide from prey or predators.

This stingray is euryhaline and can maintain adequate physiological functions at varying degrees of salinity. Stingrays found in the St. Johns River system, Florida, represent the only permanent fresh water population of an elasmobranch in North America.

Biology

Distinctive Features

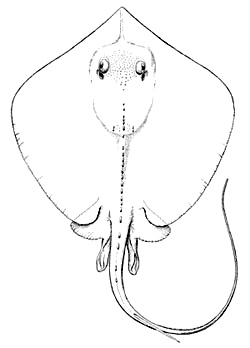

This stingray is one of the smallest rays in the family Dasyatidae. The flattened pectoral fins of the disc are continuous and extend anterior to the head and posterior to the pelvic region. Unlike most rays, the snout is elongated. The head is slightly elevated and contains spiracles that enable the ray to take in water dorsally while lying on the seabed. The gills, which expel the water, are located ventrally. The disc is approximately 1.1 times as broad as it is long. The tail is long and tapered, oval in the cross section, and extends behind the body like a whip. Dorsal and ventral tail folds are present. The dorsal fold is located posterior to the tail spine. For additional assistance in identification, see the Coastal Western North Atlantic Stingray Identification Key.

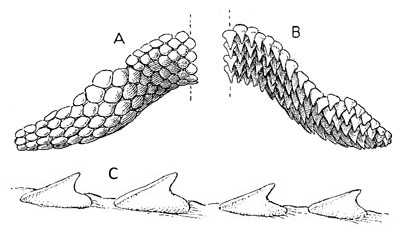

The tail spines of stingrays are thought to be modified scales, tapering to a sharp point with retrorse serations along the lateral margins. Venom is produced along two narrow grooves on both the dorsal and ventral sides. At full length, the Atlantic stingray’s tail spine is approximately 25% of its disc width, with females having longer tail spines than males. The distance between the outer margins of the eye orbits is about the same length as the tail spine. The spine is generally round but slightly flattened dorso-ventrally to a breadth of 4-5% its length. A study has shown that freshwater rays replace spines on an annual basis, usually between the months of June and October.

As with all elasmobranchs, males have two claspers, paired modifications of the pelvic fins, used in reproduction. Claspers funnel the sperm from the male to the female during the internal fertilization process.

Coloration

The Atlantic stingray is brown or yellowish brown dorsally, becoming lighter toward the disc margin, and white or light gray ventrally. The dorsal tail fold is yellowish brown while the ventral tail fold is buff. Tail coloration generally follows that of the body. However, in larger specimens the ventral portion of the tail may be flecked with gray anteriorly, and completely dark posteriorly.

Dentition

Stingrays have multiple rows of rounded teeth that have flat, blunt surfaces. The teeth of the upper jaw are largest midway along the jaw line and decrease towards the outer corners. The lower jaw has teeth of uniform size throughout. As the Atlantic stingray enters the breeding season male teeth begin to form long, slender cusps that curve toward the corners of the mouth. This enables the male to maintain an adequate hold on the female during copulation.

Denticles

Dermal denticles, characteristic of elasmobranchs, are less developed in Myliobatiformes. As the ray grows tubercles, modified scales that slope anteriorly and point posteriorly, form sporadically on the disc. These tubercles first appear across the pectoral girdle and eventually extend along the mid-line from the nuchal region to anterior of the tail spine. Post-juvenile individuals develop concentrations of flattened tubercles between the eye orbits that extend anteriorly from the eyes and posteriorly past the spiracles. Larger females may also have tubercles that occur on the outer margins of eye orbits and spiracles. These tubercles are apparently absent in males. The ventral surface is smooth in both sexes.

Size, Age, and Growth

Stingrays in Florida coastal lagoons reportedly reach a maximum disc width of 12.8 inches (32.6 cm) for males and 14.6 inches (37 cm) for females. Males mature around 7.9 inches (20 cm) disc width with females maturing at 9.4 inches (24 cm) disc width. In Freshwater populations females mature at 8.7 inches (22 cm) disc width and males mature at 8.3 inches (21 cm) disc width.

Food Habits

Dietary items differ depending on the geographical location of the population. However, prey typically consists of benthic invertebrates such as bivalves, tube anemones, amphipods, crustaceans, clams, and nereid worms. Atlantic stingrays are highly electroreceptive fish. They have rows of sensory cells call “Ampullae of Lorenzini” that are able to detect weak electric fields generated by prey items. The stingray can use this sense to locate prey buried in the sand. Scientist also believe that male stingrays may use this sense to locate buried females during the mating season.

Reproduction

Florida populations exhibit an annual protracted mating season beginning in October or November and ending in April. However, ovulation does not occur until late March or early April. During courtship, the male closely follows the female, biting at her body and fins. The male grasps the pectoral fins of the female with his teeth to assist in copulation.

Development of the embryos occurs through aplacental viviparity. When the yolk sac is absorbed, around day 60 of gestation, nourishment is provided through uterine milk from maternal secretions rather than via a placenta. Parturition occurs in late July-early August with the birth of 1-4 young.

Predators

Predators

A multitude of shark species, particularly inshore species such as the white shark, tiger shark, and bull shark, are the major predators of the Atlantic stingray. Fresh water populations are thought to be preyed upon by alligators.

Freshwater populations are known to be parasitized by Argulus sp., a fish louse, which appears to feed on the skin mucous of the Atlantic stingray.

Taxonomy

Lesueur first described this stingray as Trygon sabina in 1824. Since then it has appeared in literature under a variety of names including Pastinaca sabina, Trygon tuberculata, Dasibatis sabina, Dasybatis sabina, Dasybatus sabinus, and Amphotistius sabinus. The genus Dasyatis of the currently accepted scientific name is derived from the Greek word “dasys” meaning rough or dense and “(b)atus” meaning shark. The Atlantic stingray is a member of the Family Dasyatidae, commonly known as the “whip-tailed” rays.