Sharksucker

Echeneis naucrates

These are very recognizable fish because of their highly modified dorsal fin that is an oval shaped sucking disc. They are as long as 43 inches, and slender, with lower jaws that extend much further than upper. They attach themselves to sharks, turtles, whales, large bony fish, and sometimes ships or human divers, with the goal of eating parasites and food scraps from the host. Humans have been know to use these sharksuckers in a unique method to catch larger fish and turtles.

Order – Perciformes

Family – Echeneidae

Genus – Echeneis

Species – naucrates

Common Names

English language common names include sharksucker, live shark-sucker, live sharksucker, remora, shark remora, slender suckerfish, striped suckerfish, suckerfish, and white tailed remore. Other common names are agarrador (Portuguese), arrête-nef (French), cá chép (Vietnamese), cá Ép mãnh (Vietnamese), chasbak-mahi (Persian), chuán di yú (Mandarin Chinese), dag (Wolof), eey-maanyo (Somali), feesung (Mahl), gedemi (Malay), gemi (Malay), gemi-gemi (Malay), guaicán (Spanish), haai-remora (Afrikaans), huvudsugare (Swedish), ikan gemi (Javanese), ikan tempel (Malay), kakariuri (Tuamotuan), kemi (Hiligaynon), kimi (Banton, Kuyunon), kimmih (Chavacano), kini (Bikol, Visayan, Waray-waray, koban-zame (Japanese), kobanzame (Japanese), kolisopsaro (Greek), komi (Cebuano), kume (Waray-waray), kumi (Davawenyo), kummi (Maranao/Samal/Tao Sug), lablab (Misima-Paneati), lampe (Kagayanen), lapador (Creole, Portuguese), lattil bako (Marshallese), lazak (Arabic), lazzag (Arabic), lizzag (Arabic), mbuzi-bahari (Swahili), nián chuán yú (Mandarin Chinese), pandawan (Tagalog), parikit banca (Tagalog), parikit-banka (Tagalog), parikit-ugit (Tagalog), pega (Spanish), pegador (Portuguese), pegador-listado (Portuguese), pegatimon (Spanish), peixe-pegador (Portuguese), peixe-piolho (Portuguese), peixe-sapato (Portuguese), pelx ventosa (Catalan), picardo (Krio), piga-piga (Pangasinan), pilote (French), pilote-requin (French), piolho (Portuguese), piolho de tubarão (Portuguese), piolho-de-cação (Portuguese), piraquiba (Portuguese), podnawka (Polish), poisson pilote (French), ppal-p’an-sang-o (Korean), qamly (Arabic), raorago bagea (Gela), rémora (French), rémora commun (French), rémora rayada (Spanish), remora tal-faxx (Maltese), remora tal-faxx iswed (Maltese), rémora tiburonera (Spanish), rumi-rumi (Malay), sangazzuga (Italian), schiffshalter (German), stribet sugefisk (Danish), takegal (Wolof), talitaliuli (Samoan), tamwilemwil (Carolinian), tapak kasut (Malay), thowâng (Nemi), ti’ati’auri (Tahitian), vantuz baligi (Turkish), xi pán yú (Mandarin Chinese), xudu (Nemi), yìn (Mandarin Chinese), yìn tóu yú (Mandarin Chinese), and zicca (Italian).

Importance to Humans

Although the sharksucker is of minor commercial importance, it is considered a gamefish by recreational fishers. It is also captured and displayed in public aquaria facilities.

An interesting aspect of the importance of this unique fish to humans is that it is used by natives to catch other fish. A fishing line is tied to the caudal peduncle of the sharksucker, which is then released, into the deep sea. When the sharksucker attaches to another fish, the sharksucker and its host is then hauled in to land or to the boat by the fisher. This helps fishers acquire marine organisms that are typically difficult to catch.

Danger to Humans

Although considered harmless to humans, there have been some reports on sharksuckers following divers and attaching to divers’ legs. It is extremely painful to have a sharksucker attach by the sucking disc with numerous sharp ridges to a human body. There have also been reports of sharksuckers causing damage to boats by attaching to the hulls with their sucking discs, damaging the boat even to the point of even sinking it.

Conservation

The sharksucker is not listed with the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Red List. The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species. It is a very common fish with a wide distribution and is not in any imminent danger of becoming threatened or endangered.

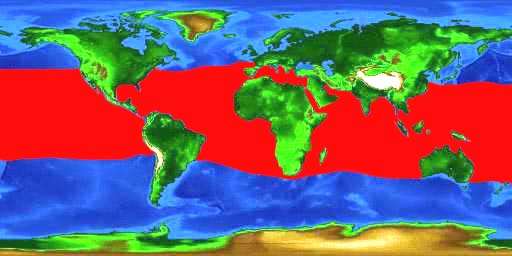

Geographical Distribution

This unusual fish has a wide distribution range including the Pacific Ocean north to San Francisco, California and in the Indian Ocean. It is also commonly observed from southwestern Western Australia and around the tropical north and south to the southern coast of New South Wales. It is less often observed in waters off Victoria and Tasmania. In the western Atlantic Ocean, the sharksucker is found from Nova Scotia, Canada east to Bermuda and south to Uruguay.

Habitat

This fish is the most abundant remora and is found in inshore as well as offshore in tropical and warm temperate waters at depths from 66-164 feet (20-50 m). Although known for attaching to a variety of hosts including sharks, rays, large bony fishes, sea turtles and marine mammals as well as sometimes ships, the sharksucker is often observed in free-swimming groups over shallow coral reefs. This species is dependent upon their hosts for survival as they are a poor swimmer and lack a swim bladder. It attaches to the host beginning early in their lives with a modified dorsal fin that is used as a sucking disc. Sharksuckers typically attach themselves onto either the body or the gill region of the host. There have been documented sightings of sharksuckers traveling up freshwater rivers while attached to a host.

Biology

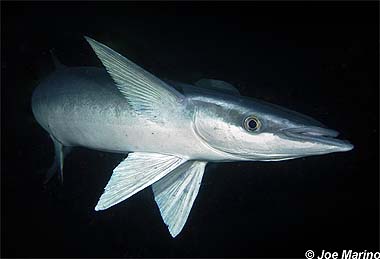

Distinctive Features

The modified dorsal fin used as a sucking disc to attach to hosts makes the sharksucker easy to distinguish from other fish. This oval-shaped sucking disc consists of 16-28 laminae and is positioned from the top of the head to the anterior portion of the body.

The sharksucker has a long slim body, measuring 11 or 12 times as long as it is wide. The lower jaw of the sharksucker projects forward beyond the upper jaw. The dorsal fin and anal fin originate at the midlength of the body and taper, extending almost to the base of the caudal fin. The caudal fin of mature specimens is almost truncate with the upper and lower lobes longer than the middle rays. The pectoral fins are located high on the sides of the body with upper margins overlapping the edge of the sucking disc. The dorsal and anal fins have long bases with elevated leading rays. It is difficult to distinguish male and female specimens. The young begin to resemble the adults upon the formation of the sucking disc.

Coloration

The long slim body of the sharksucker is dark gray or dark brownish gray with a dark belly. There is a broad darker brown or dark gray stripe with white edges on each side that extends from the jaw to the base of the caudal fin with interruptions from the eyes and pectoral fins. The pectoral fins and ventral fins are black with or without a pale edge while the dorsal and anal fins are dark gray or black with white margins. The caudal fin is black with distinct white corners.

Dentition

The jaws of this sharksucker contain a vomer and numerous pointed villiform teeth.

Food Habits

The sharksucker attaches to a variety of hosts including sharks, rays, large bony fishes, sea turtles, whale, dolphin, and even sometimes to ships. During this time of attachment, the sharksucker feeds on food scraps from the host’s feeding activities as well as small crustaceans parasites on the host’s skin. This diet is supplemented with free-living crustaceans, crabs, squid, and small fishes. Juvenile sharksuckers sometimes act as cleaning fish, setting up cleaning stations where they clean parasites off parrotfishes. In captivity, the sharksucker can be feed pieces of clam and fish by hand.

Reproduction

Spawning occurs during the spring and summer months throughout most of its range and during the autumn months in the Mediterranean Sea. The eggs are fertilized externally followed by enclosure of a hard shell, which protects them from damage and desiccation. These pelagic eggs are large and spherical in shape. When the embryos hatch, each measures 0.18-0.30 inches (.47-.75 cm) in length. These young fish have a large yolk sac, non-pigmented eyes, and an incompletely developed body. During development of the newly hatched fish, the sucking disc begins to form. Small teeth appear on the upper jaw and large teeth on the lower jaw during this period. Immature sharksuckers live freely for about one year until reaching approximately 1.2 inches (3 cm) in length at which time they attack to a host fish.

Predators

Sharksuckers have no known predators.

Parasites

Very little is known about the parasites of the sharksucker.

Taxonomy

Linnaeus originally described the sharksucker as Echeneis naucrates in 1758. The genus name, Echeneis, is derived from the Greek ‘echein’ meaning to hold and ‘nays’ meaning ship; remora, suckling fish. In ancient Greece, sailors feared that sharksuckers had mysterious magical powers and could slow down or stop their ships. Synonyms referring to this species in past scientific literature include Echeneis lunata Bancroft 1831, Echeneis vittata Rüppell 1838, Echeneis fasciata Gronow 1854, Echeneis fusca Gronow 1854, Echeneis guaican Poey 1860, Echeneis metallica Poey 1860, and Leptecheneis flaviventris Seale 1906.

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester