Nassau Grouper

Epinephelus striatus

These large, oblong fish can change both color and gender, and live at the rocky reef bottom of tropical Western Atlantic waters. They are usually a light buff to pink color with striking darker bars and spots, but can change to very light or very dark quickly. There is some debate, but they are protogynous hermaphrodites, meaning most start out as females and then become males after a few years of spawning. They grow up to 4 feet long and eat mostly crustaceans and other smaller fish by opening their mouths and inhaling them.

Order: Perciformes

Family: Serranidae

Genus: Epinephelus

Species: striatus

Common Names

English language common names include Nassau grouper, day grouper, grouper, hamlet, rockfish, sweet lip, and white grouper. Other language common names are cherna (Spanish), cherna criolla (Spanish), granik siodlasky (Polish), jacob peper (Dutch), jocupepu (Papiamento), mero (Spanish), mero gallina (Spanish), merou raye (French), nagul (French), negue, tienne (French), vieille (French), yakupepu (Papiamento).

Importance to Humans

This fish is considered an important food fish throughout the Caribbean and in the West Indies. Hook and line as well as traps are the main methods used to capture the Nassau grouper. The flesh is primarily marketed as fresh, however there have been reports of ciguatera poisoning from human consumption of this fish.

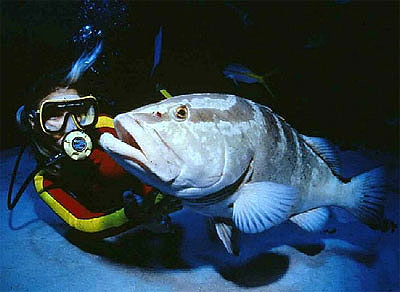

Divers interact with unwary, curious groupers that are easy to feed. They are favorite subjects of underwater photographers due to their zebra-like coloration.

Danger to Humans

There have been reports of ciguatera poisoning from human consumption of Nassau groupers. Ciguatera poisoning is caused by dinoflagellates (microalgae) found on dead corals or macroalgae. By feeding on these corals and macroalgae, herbivorous fishes accumulate a toxin generated by these dinoflagellates. Largely a phenomenon of tropical marine environments, ciguitoxin accumulates still further in snappers and other large predatory reef species that feed on these herbivorous fishes. If accumulated levels of the toxin are great enough they can cause poisoning in humans whom consume the flesh of these fishes. Poisoned people report having gastrointestinal problems for up to several days, and a general weakness in their arms and legs. It is very rare to be afflicted with ciguatera poisoning.

Conservation Status

Currently all harvest of the Nassau grouper is prohibited in the U.S. It is also listed as a candidate for the U.S. Endangered Species List. The Nassau grouper has been heavily fished and vulnerable to overfishing. The spawning aggregations that appear at the same site each year are easy targets for fishers. During these spawning events, the reproductively mature fish are often caught. This further limits potential population growth through the removal of mature females, leaving behind the young females that release fewer eggs for fertilization.

> Check the status of the nassau grouper at the IUCN website.

The Nassau Grouper is currently assessed as “Endangered” by the World Conservation Union (IUCN). The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Download the NOAA Technical Report on the Nassau grouper and related goliath grouper.

Geographical Distribution

The Nassau grouper is found throughout the tropical western Atlantic Ocean, including Bermuda, Florida, Bahamas, and throughout the Caribbean Sea, south to Brazil. Occurs in the Gulf of Mexico in limited locations including the Yucatan, Tortugas, and Key West.

Habitat

This grouper is common on offshore rocky bottoms and coral reefs throughout the Caribbean region. They occur at a depth range extending to at least 295 feet (90 m), preferring to rest near or close to the bottom. Juveniles are found closer to shore in seagrass beds that offer a suitable nursery habitat. Nassau groupers are typically solitary and diurnal, however, they may occasionally form schools. When threatened by predators, this fish can camouflage itself, blending in with the surrounding rocks and corals. Groupers are frequent visitors to wrasse cleaning stations. At these stations, cleaner wrasses pick parasites and dead tissues from the grouper’s gills and body. The grouper will open its mouth in a non-threatening manner, attracting cleaner fish to enter its mouth to remove parasites.

Biology

Distinctive Features

The Nassau grouper is an oblong, large fish with large eyes and coarse, spiny fins. The third or fourth spine of the dorsal fin is longer than the second spine. Pelvic fins are shorter than the pectoral fins, with the insertion point located below or behind the ventral terminus of the pectoral fin base. The bases of the soft dorsal and anal fins are covered with scales and skin. Caudal fin is rounded in juveniles, convex in adults.

Coloration

This grouper has a light, buff background color in shallow water individuals, pinkish to red in those from deeper water. There are five irregular dark brown vertical bars on each side and a large black saddle on the top of the caudal peduncle. The third and fourth vertical bars form a W-shape above the lateral line. A tuning fork-shaped mark is located on the forehead. Another dark band travels from the snout through the eye, curving up to meet the same band from the other side, just before the dorsal fin origin. Black dots are located around the eyes. This is some variation among individuals, as some fish may have irregular pale spots on the head and body. The Nassau grouper can change color pattern from light to dark brown very quickly, depending upon the surrounding environment and mood of the fish. Another color pattern is observed in the Nassau grouper when two adults or an adult and large juvenile meet. The smaller individual displays a bicolored pattern, with a dark head and white fins, caudal peduncle, and ventral body. There is a white band that reaches from the snout, past the eye towards the dorsal fin. After swimming away, the bicolored fish resumes its normal barred pattern within minutes. This same bicolored pattern is observed in aggregations of spawning fishes, perhaps indicating a peaceful, non-territorial state.

Dentition

Groupers have several sets of strong, slender teeth that act as raspers. These teeth are not used to tear flesh as with the barracudas and sharks, but rather to prevent small fish from escaping.

Size, Age, and Growth

Growing to a maximum of 4 feet (1.2 m) and weighing over 50 pounds (22.7 kg), this grouper is one of the largest fish on the reef. More commonly, this grouper reaches a length of 1-2 feet (.3-.6 m) and weighs 10-20 pounds (4.5-9 kg). The maximum age reported for this fish is 16 years.

Food Habits

As a carnivorous predator, the Nassau grouper has a diet that consists mainly of fish, shrimps, crabs, lobsters, and octopuses. Prey fish include parrotfishes, wrasses, damselfishes, squirrelfishes, snappers, and grunts. This clever fish patiently waits in hiding, utilizing its ability to camouflage, until it pounces on its prey. By opening its mouth and dilating the gill covers to draw water in, groupers generally engulf their prey hole in one quick motion. An interesting note, as a friendly, unwary fish, if offered food by divers it will repeatedly return searching for more food handouts.

Reproduction

The Nassau grouper forms large spawning aggregations from a few dozen to over 100,000 individuals. These aggregations form in depth of 65-130 ft (20-40 m) on the outer shelf near the full moon during the winter months. During the spawning event, most fish display the bicolored pattern and swim near the bottom. Some females remain in the barred color pattern and become very dark as mating approaches. A group of bicolored males swims in circles near the female upon sunset. Courtship behavior includes vertical spirals, short vertical runs followed by crowding together and rapid dispersal, and horizontal runs near the bottom. Release of gametes is initiated by the female moving in a rapid forward and upward direction. The eggs are released by the female, followed by the release of sperm by all the following bicolored males as well as further release of eggs by some bicolored females. This is known as the “spawning rush”. Fertilization occurs by chance in the open waters, large spawning aggregations further improve these chances. One such aggregation was reported in the Bahamas which included as many as 100,000 fish.

Groupers are protogynous hermaphrodites. After spawning as a female for one or more years, the grouper changes sex, functioning as a male during future spawning events. Individuals of the Nassau grouper have been discovered to be male without previously going through a female stage and are smaller than the secondary males. It is believed by some that the sex change is triggered when the fish aggregate in preparation for spawning. It is difficult to distinguish different species of grouper larvae from one another, since what information is known about egg and larval development is general. The eggs hatch into pelagic larvae that drift along with the currents for a month or so, prior to becoming juveniles. The larvae are characterized by kite-shaped bodies and elongated second dorsal spines. Juveniles settle at lengths of approximately 32mm, residing in vegetated areas near coral clumps. At 120-150mm in length, the juvenile Nassau groupers move out from vegetated areas to surrounding patch reefs.

Predators

Predators of the Nassau grouper include large fish such as barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda), king mackerel (Scomberomorus cavalla), moray eels (Gymnothorax spp.), and other groupers. The sandbar shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus) and the great hammerhead shark (Sphyrna mokarran) are also known to feed on groupers.

Parasites

Nassau groupers are host to a variety of parasitic organisms including isopods located in the nostrils, larval tapeworms in the viscera, and nematodes in the ovaries. These nematodes can have negative impact on the numbers of eggs produced by female Nassau groupers. The impact of these parasites on the health of the host is relatively unknown. Nassau groupers also frequent “cleaning stations” on coral reefs. At these stations, gobies and shrimps remove isopods from the bodies, fins, mouths, and gills of these groupers and other fish.

Taxonomy

Epinephelus striatus was first described by the German Ichthyologist Marcus Eliese Bloch in 1792. The genus name comes from the Greek Epinephelus meaning clouded over while striatus is Latin, referring to the striped color pattern. Synonyms include Anthias cherna Bloch and Schneider 1801, Sparus chrysomelas Lacepede 1802, and Serranus gymnopareius Valenciennes 1828.

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester