Cownose Ray

Rhinoptera bonasus

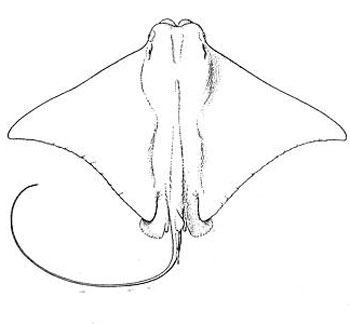

This unique ray is dark brown to golden brown on top, and white below, with a stout body and triangular ‘wings’. The distinct lobes on the front edge give it the name cownose, and the long sturdy tail has one or two serrated spines with mild venom. Their tile-like teeth are ideal for crushing crustaceans and mollusks, as well as small invertebrates and bony fish.

The cownose rays prefer shallow, brackish water, but tend to swim at the surface, reducing the risk of humans stepping on them. They are known to school in large groups to migrate great distances, an event popular with divers and photographers.

Order: Myliobatiformes

Family: Rhinopteridae

Genus: Rhinoptera

Species: bonasus

Common Names

English language common names include cowfish, cownose ray, and skeete. Other common names are cara de vaca (Spanish), chucho (Spanish), echte koeneusrog (Dutch), gavilan mancha/manchado (Spanish), kurogane-ushibana-tobi-ei (Japanese), lehmärausku (Finnish), mancha (Spanish), manta (Spanish), mourine amèricaine (French), raia-focinho-de-vaca (Portuguese), raia-sapo (Portuguese), raya gavilán (Spanish), ray sparrowhawk (Spanish), spot (Spanish), and ticonha (Portuguese).

Importance to Humans

There has been concern about the increasing population size of cownose rays due to their high predation of oyster beds. The oyster population has been decreasing due to diseases and pollution reducing their grass bed habitat. It is thought that the cownose ray’s high predation of oyster beds could further complicate the problem of declining oyster populations.

The Virginia Sea Grant Marine Advisory Program has considered solving this problem by proposing commercial fishing of cownose rays. Commercial fishing of this species has not yet been established because of many possible problems associated with it. There is currently no market for cownose rays even though participants in a taste test liked the cownose ray meat.

The harvesting and processing of these rays is quite difficult, which could result in the meat being too expensive to sell. They are also vulnerable to over fishing since they mature relatively late and have low levels of reproduction. Cownose rays may be the cause of some problems, but they are also an important part of the ecosystem.

Danger to Humans

The cownose ray differs from other ray species in that it rarely rests on the bottom, minimizing the chance that someone might step on the spine. The potential of being hurt from this ray flicking its tail is minimal since the spine is located on the tail close to the ray’s body.

Shigella may be acquired from eating cownose ray meat that has been contaminated with this bacteria. This bacteria causes shigellosis that results in dysentery, which include the symptoms of diarrhea, pain, fever, and possible dehydration.

Conservation

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), the cownose ray is listed as “Near Threatened”. The IUCN consists of a global union of state, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in partnership whos goal is to assess the conservation status of different species.

> Check the status of the cownose ray at the IUCN website.

Geographical Distribution

The distribution of the cownose ray includes the eastern Atlantic Ocean including Mauritania, Senegal, and Guinea. They are also located in the western Atlantic from southern New England to northern Florida (USA) and throughout the Gulf of Mexico, migrating to Trinidad, Venezuela, and Brazil.

Habitat

This pelagic species is also sometimes found in inshore waters. For the most part, this species is known for its migrations to different parts of the ocean (oceanodromous). The environments in which they are found include brackish and marine habitats. They are found at depths to 72 feet (22 m). They are gregarious and make long migrations.

The cownose ray population is believed to be increasing in numbers. The migration patterns, in the Atlantic, include a northward movement in the late spring and southward movements in the late fall. Southbound migration has been observed to contain larger schools than the northbound migration. Smith and Merriner (1987) believe that the changes in water temperature, coupled with sun orientation, may initiate seasonal mass migration.

They also suggest that the southward migration might be influenced by solar orientation while the northward migration might be influenced by water temperature cooling below 22ºC, but further studies are needed to confirm this. The migratory congregation, thus far, has not been linked to feeding or premigratory mating activity.

Biology

Distinctive Features

This ray is set apart from all of its relatives by the indented anterior contour of its cartilaginous skull (chondrocranium), with the conspicuously bilobed subrostral fin. The exception to this is the ticon cownose ray (Rhinoptera brasiliensis), which so closely resembles R. bonasus in both appearance and bodily proportions, that they can only be differentiated by their number of teeth. Normally, R. bonasus has only seven series in each jaw while the ticon cownose ray has nine.

The disc is approximately 1.7 times as broad as it is long. The eyes and the spiracles of the cownose ray are located on the sides of their broad head. The main portions of the pectorals arise from the sides of the head, close behind and below the eyes. The outer corners of the pectorals are pointed and become concave toward their posterior margins. The dorsal fin originates approximately opposite the rear ends of the bases of the pelvic fins and is rounded above.

The tail, round to oval in cross-section, is moderately stout near the anterior spine, and narrows rearward, tapering to a lash-like tip. The length of the tail, measured from the center of the cloaca, is about twice as long as the body, measured from the cloaca to the front of the head, but can be three times as long on small specimens. There are one or two tail spines. The first spine (posterior spine) is located directly behind the base of the dorsal fin. If present, the second spine (anterior spine) has a free portion that is about half as long as the anterior margin of the pelvic fin.

The anterior spine varies in length from very short (tip hardly emerges from skin) to as long as the posterior spine. The spines contain marginal teeth with broad bases and sharp tips that curve rearward at a 45º angle. The number of teeth ranges from 22 to 45. The spine processes toxins and mucous into its ventral grooves, which is produced from spongy venom glands located along the underside of the spine.

Coloration

The dorsal surface of the cownose ray is light to dark brown, and can sometimes have a yellowish tint. The ventral surface is white or yellowish white with the outer corners of the pectorals being more or less brownish. Some specimens are marked above and below with many narrow obscure dark lines or bands that radiated outward from the center of the disc. Tail coloration generally follows that of the body.

Dentition

There are usually 7 series of teeth, on the dental plate, in each jaw that contain up to 11 to 13 rows exposed and functioning simultaneously. The edges of the teeth vary with the median five series being hexagonal, the outermost series being pentagonal, and the supernumerary series being tetragonal.

Denticles

Skin, apart from the tail spines, is smooth at all ages.

Size, Age, and Growth

The disc width at birth is about 14 inches (36 cm). There seems to be a considerable variation in the size when maturity is reached, which is independent from geographical influence. A male from the North Carolina waters measured only 26-28 inches (66-71 cm) wide with testes enlarged, whereas a Brazilian male measured 31 inches (79 cm) having the claspers only reach about halfway along the inner margins of the pelvic fins. A female containing embryos measured 24 inches (61 cm). The maximum size that this species ordinarily grows is debated but a disc width of 84 inches (213 cm, male/unsexed) has been recorded.

Food Habits

The diet of the cownose ray population in the Chesapeake Bay, Virginia consists primarily of bivalve mollusks. They eat the mollusks by crushing the shells between their terrazo-like tooth plates. Through examination of the cownose rays stomachs and spiral valves, there were large quantities of crushed valves of thin-shelled bivalves, small to moderate amounts of bivalves with intermediate thickness, and only a few small valve fragments of the thick-shelled. It has been suggested that the buccal papillae are instrumental in sorting the shell fragments from the shellfish meats.

It has been proposed that cownose rays use a very specific mechanism to obtain deep-burrowing prey. They locate food on the bottom substrate (benthos) through mechano- or electroreceptive detection. Once they suspect prey is there, they employ a combination of stirring motions of the pectorals while sucking/venting both water and sediment out through the gills and away from the area to create a central steep-sided cavity depression. The continued movement of the pectoral fins aids in dispersing the sediments released from the gills and increases the depth of the depression. Eventually, the food is seized and drawn into the mouth.

Common prey items include nekton, zoobenthos, finfish, benthos crustaceans, mollusks, bony fish, crabs, lobsters, bivalves, and gastropods.

Reproduction

The breeding period is considered to be June through October. According to observations in July of 2000 by biologists from the NMFS Apex Predators Program, a large school of cownose rays of varying ages and sexes was spotted in the shallows of Delaware Bay. A female cownose ray was seen swimming with the edges of her pectoral fins sticking out of the water. Upon closer observations, up to 6 male cownose rays were following her, trying to grasp the pectoral fins to mate.

Occasionally, there would be major splashing as the males tried jumping out of the water to grasp the pectoral fins with their mouths. It is thought that the female’s having the pectoral fins out of the water might be mate avoidance behavior.

The exact gestation period is not currently known for the cownose ray. The gestation period is believed to be 11-12 months, although some evidence suggests that cownose rays might have two gestation periods lasting 5-6 months. Development is ovoviviparous, producing eggs that develop within the maternal body and hatch within. The embryos lose the shell capsule in early August. Studies have shown that by the third quarter term, the embryos are upright in the uterus with the rostrum facing forward, pectoral fins folded dorsally, and the tail with the heavily sheathed spine is bent forward along the dorsal side of the disc.

The initial nutrition provided to the embryos is from the yolk, which gradually diminishes between August and October. After October, histotroph, a viscid yellowish secretion from the uterus, provides the remaining nutrition. It is assumed that the embryos receive this through the mouth, spiracles, and gill slits.

It is suspected that only one cownose ray embryo is carried to full term but six embryos have been found to make it to full term in one female. Following parturation, females will typically ovulate.

Predators

Some of the predators that are known to prey on cownose ray include cobia (Rachycentron canadum), sandbar shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus), and bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas).

Parasites

Common bacteria found in cownose ray include Shigella sp. (in intestine) and Serratia liquefaciens (on teeth). Shigella sp. causes inflammatory dysentary (Shigellosis). It is believed that Serratia liquefaciens may be an opportunistic pathogen in this species but has been found to be pathogenic to some salmon and Arctic Char.

Cestodes (tapeworms) have been found in cownose rays. Most of these cestodes infect the spiral valve of the cownose ray. The most commonly found cestodes include Rhinoptericola megacantha, Dioecotaenia campbelli, Rhodobothrium paucitesticulare, Eiweria southwelli, and Tylocephalum sp.

Benedenella posterocolpa, a monogenetic trematode, has been found on the ventral surface of cownose rays. These trematodes will typically fall off in salinities 28 0/00 or higher.

Taxonomy

The cownose ray was first named Raja bonasus (Mitchill, 1815). This name was changed to the currently valid name Rhinoptera bonasus that same year. The genus name is derived from the Greek “rhinos” meaning nose and “pteron” meaning wing. The species name bonasus is from the Greek “bonasos” meaning bison. Synonyms include Rhinoptera lalandi (Müller and Henle, 1841) and Rhinoptera affinis (Bleeker, 1863) along with a misidentification as Rhinoptera javanica (non Müller and Henle, 1841).

Prepared by: Kimberly Kittle