Coral reef communities within Florida waters are categorized as:

- Hardbottom

- Patch Reef

- Bank Reef

Hardbottom Community

- Close to shore

- Low species diversity

- Dominated by gorgonians, algae, and sponges

Hardbottom reef communities are found close to shore over limestone rock covered by a thin sandy layer. Hardbottom communities have low species diversity, dominated by gorgonians, algae, sponges, and a few stony coral species. Hardbottom habitats provide important cover and feeding areas for many fish and invertebrates.

Hardbottom communities are often divided into two types:

- Nearshore restricted hardbottom communities are subject to limited water movement. This bottom community is dominated by algae including epilithic algae that attaches itself directly to the limestone bottom as well as drift algae.

- Nearshore high-velocity hardbottom communities are exposed to strong currents. Gorgonians, easily recognized with their rod-like appearance and flexibility, and sponges dominate these communities.

Stony corals have adaptations, including a mucous layer used to removed sediments from their polyps, enabling them to survive in these communities.

These coral species include:

- smooth starlet coral (Siderastrea radians)

- golfball coral (Favia fragum)

- elliptical star coral (Dichocoenia stokesii)

- common brain coral (Diploria strigosa)

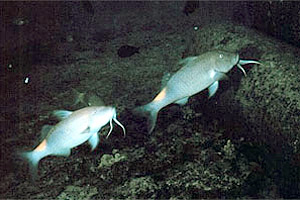

A variety of other animal species, including anemones, mollusks, crabs, seastars, sea cucumbers, spiny lobsters, and fish, are associated with hardbottom communities. Fish that forage in these areas include grunts (Haemulon spp.), snappers (Lutjanus spp.), groupers (Epinephelus spp.), and great barracudas (Spyraena barracuda). Tangs (Acanthurus coeruleus) and surgeonfish (Acanthurus bahianus) form large feeding schools over hard bottoms.

Gorgonians provide an increase in surface area for attachment of invertebrates including tunicates, anemones, mollusks, and worms.

Spiny lobster. Photo courtesy NOAA

Spiny lobster. Photo courtesy NOAA French grunt. Photo © Dr. Antonio J. Ferreira, California Academy of Sciences

French grunt. Photo © Dr. Antonio J. Ferreira, California Academy of Sciences Sea anemone. Photo © Mark Younger

Sea anemone. Photo © Mark Younger Seastar. Photo © Leroy Ellis

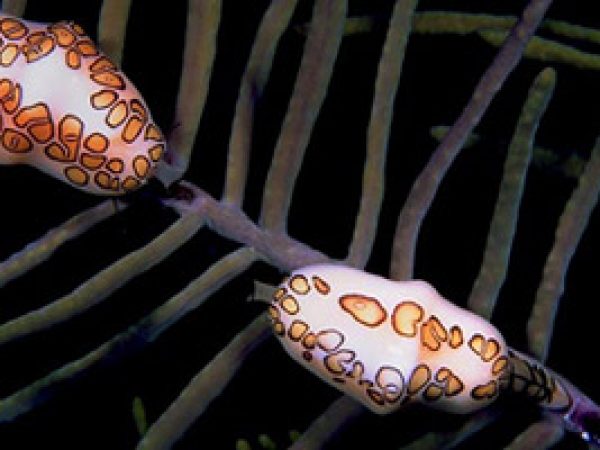

Seastar. Photo © Leroy Ellis Flamingo tongues living on a gorgonian. Photo courtesy Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

Flamingo tongues living on a gorgonian. Photo courtesy Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary

Patch Reef Community

- Located in shallow water 10-20′ (3-6 m)

- Outer edge ringed by sand

- Dominated by large star and brain coral colonies

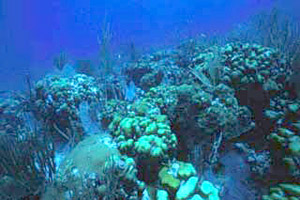

Patch reefs are located in shallow waters of 10-20 feet (3-6 m) in depth, within the Florida Reef Tract. The outer edge of each patch reef is surrounded by a halo of sand that extends out to adjacent seagrass beds. The width of this ring of sand is determined by the distance that herbivorous fish feel is within safe foraging range from the reef. Each patch reef differs in size, development, and species residing on them.

The patch reef originates with a coral larva settling out of the plankton onto a hard surface for attachment. It develops into a moderate-sized coral colony over time. Eventually the coral dies, perhaps from storm or predator damage, leaving behind the calcium carbonate skeleton upon which more coral larvae can settle. This continues for hundreds of years with the reef expanding upwards, towards the water’s surface. As the reef reaches the surface, it will begin growing outward rather than upward.

Large colonies of star and brain corals (Montastraea annularis, Siderastrea siderea, and Diploriaspp.) form the base of many patch reefs, with smaller coral species settling on any exposed dead coral. Boring sponges, worms, and mollusks excavate through the coral skeleton, forming crevices that provide refuge for fish and invertebrates. Over time, the underlying foundation of the reef weakens resulting in the collapse of the structure.

Reef fish commonly found along the top of patch reefs include:

- bluehead (Thalassoma bifasciatum)

- surgeonfish (Acanthurus bahianus)

- French angelfish (Pomacanthus paru)

- queen angelfish (Pomacanthus arcuatus)

- white grunt (Haemulon plumieri)

- yellowtail snapper (Lutjanus chrysurus)

- stoplight parrotfish (Sparisoma viride)

Among the coral heads and branching corals are:

- bluehead (Thalassoma bifasciatum)

- sergeant major (Abudefduf saxatilis)

- Spanish grunt (Haemulon macrostomum)

Trumpetfish (Aulostomus maculatus) and filefish can be observed standing vertically among gorgonian branches. Larger predatory fish including grouper (Epinephelus spp.), snapper (Lutjanus spp.), bar jack (Caranx ruber), and great barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda) search for prey in the water above the reef formation.

Bank Reef Community

- Located seaward from patch reefs

- High species diversity

- Characterized by spur and groove formation

Bank reefs form an elongate, broken arc from Miami south along the Florida Keys to the Dry Tortugas. Located further toward the sea than the patch reefs of nearshore environments, bank reefs are significantly larger than patch reefs and are common dive and snorkel destinations.

On the inshore side of the bank reef is the reef flat. This area consists of broken coral skeletons and coralline algae. Seaward from the reef flat is the spur and groove formation consisting of low ridges of corals (spurs) separated by sandy bottom channels (grooves). Within shallow areas, the bottom substrate is colonized by fire corals and zoanthids. With increase of water depth to five or six feet (1.5-1.8 m), elkhorn (Acropora palmata), star (Montastraea annularis), and brain corals (Diploria spp.) dominate the surface of the reef. Sea fans, seawhips, and sea plumes are also common in this area. The sand grooves running between the spurs consist primarily of shells and fragments of coral and algae that make up the coarse white limestone sand. These grooves are habitat for many invertebrates which remain hidden in the sand during the day, sneaking out under the cover of night to search for food.

Zoanthid. Photo courtesy NOAA

Zoanthid. Photo courtesy NOAA Elkhorn coral. Photo courtesy Paige Gill, Florida National Marine Sanctuary

Elkhorn coral. Photo courtesy Paige Gill, Florida National Marine Sanctuary Star coral (Montastraea annularis) polyps. Photo © Mark Younger

Star coral (Montastraea annularis) polyps. Photo © Mark Younger Common brain coral. Photo © Don DeMaria

Common brain coral. Photo © Don DeMaria Plate coral. Photo © Eugene Weber, California Academy of Sciences

Plate coral. Photo © Eugene Weber, California Academy of Sciences

Further out from the spur and groove zone is the forereef zone. This area, dominated by star coral (Montastraea annularis), is inhabited by a variety of benthic organisms. The reef then slopes deeper into the sea where light becomes a limiting factor. At these depths, corals adapt to lower light levels by growing in flat, plate-like formations. At depth further increases, the reef drops off rapidly into the depths. Sunlight gradually disappears, resulting in a community of sponges and non-reef building corals.

Common inhabitants of the outer bank reefs include:

- French angelfish (Pomacanthus paru)

- blue parrotfish (Scarus coeruleus)

- queen triggerfish (Balistes vetula)

- rock beauties (Holacanthus tricolor)

- porkfish (Anisotremus virginicus)

- snappers (Lutjanus spp.)

Fish frequent the reef during different times of the day. Many fish leave the protection of the reef at night to venture out to the nearby seagrass beds in search of food while other species, such as the parrotfish, settle down for the night within the reef structure. Parrotfish build a mucus cocoon that surrounds them at night while they sleep. If the cocoon is disturbed, the fish immediately awakens and dashes off, escaping any potential predators.

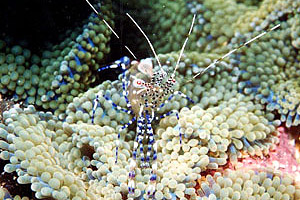

Cleaning stations are maintained by a number of small organisms including wrasses, gobies, and small shrimp. Larger fish visit this station to have their teeth cleaned and external parasites removed. These fish signal through body movements and postures, letting the cleaners know that they are ready to have their mouths and gill chambers cleaned. This relationship benefits the visiting fish as well as the cleaners.

Glossary terms on page

- diversity: refers to the variety of species within a given association, areas of high diversity are characterized by a great variety of species.

- algae: a diverse group of photosynthetic organisms that lack roots, stems, leaves, and vascular tissues.

- gorgonian: a type of octocoral (soft coral) commonly found in southeast Florida reefs at depths less than 30 meters; they include sea fans, sea plumes, sea whips, and sea rods.

- Florida Reef Tract: the third largest barrier reef in the world, running from the Miami area southwest to the Dry Tortugas.

- plankton: organisms dependent on water movement and currents as their means of transportation, including phytoplankton, zooplankton, and ichthyoplankton.

- calcium carbonate: compound consisting of calcium and carbonate with a chemical structure of CaCO3.

- larvae: immature form of an animal that undergoes metamorphosis prior to changing into the adult form.

- coralline algae: algae that secrete calcium carbonate in their tissues. Hard, encrusting, red coralline algae are significant reef builders in some areas.

- zoanthid: generally small anemone; may be colonial or solitary, and both symbiotic and free-living.

- substrate: the material upon or within an organism lives or grows, including soil, plants, animals and rocks.

- benthic: pertaining to organisms that live on rock or sediment beneath a body of water.